t is an open secret in the watch industry: a large proportion of watches bearing the label of big names are actually produced by third parties. Welcome to the fascinating world of private label, the “behind-the-scenes” of watchmaking. It is worth looking at the major changes that the companies in this segment are undergoing. These changes are indeed indicative of fundamental breaks in the industry.

Smaller series and faster production for a higher final price: roughly speaking, this is the trend that the private label company must follow in order to cope with changing times. Indeed, the Swiss watch industry is producing less and less volumes, while at the same time reaching higher value. Other private label specialists, mainly in Asia, are focusing on fashion watches and a more entry-level production. They too encounter strong headwinds (read more about them below).

-

- The assembly lines of Timepieces (FM Swiss Logistics Group) in Ticino

Smaller series and faster production for a higher final price: roughly speaking, this is the trend that the private label company must follow in order to cope with changing times.

The discreet side of the industry

Jérôme Biard recently took over the reins of one of the most prestigious companies in the segment, Roventa-Henex, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2019. Formerly with Richemont Group, Girard-Perregaux and then Corum and Eterna, the manager is moving to the backstage. And it’s not necessarily a bad thing...

-

- Jérôme Biard, CEO of Roventa-Henex

“To be honest, I didn’t know much about this side of the business,” he explains. “It’s actually the opposite of a brand, where everything is shouted in capital letters. When you’re working on the product exclusively, like we do, you’re on the right side of the curtain: there’s a huge amount of know-how, with some employees who’ve been with us for forty years, a lot of humility, true love of the product, and absolutely no management of egos. We are artisans in the shadows and we follow the old adage to live happily, let’s live hidden!”

A pioneer of the private label segment based in Biel and Tavannes, Roventa-Henex employs 90 people in Switzerland and 8 people in Hong Kong for an annual production of around one million units. The company underwent a management buyout in 1997, before the German investment fund Findos Investor took control in 2013. At the time, many watch brands were integrating their production, with most of them seeking to proclaim themselves “manufactures”. A word that sounds like the enemy for private label companies, which instead seek to convince brands of the benefits of outsourcing their production. Today, the trend is much more favourable to them.

-

- Roventa-Henex in 1989 in Europa Star

Back to better days

“About five years ago, we started seeing a strong inversion of the business cycle, with the trend for integration running out of steam,” says Christine Le Marquand, sales and marketing director at Walca, another big name in the private label world based in Biel - the family company has produced more than 10 million units since it was founded in 1976. “Many watch brands realised that investments in in-house production were too expensive for them at the end. Moreover, we offer unique advantages: a strong technical expertise, as well as in-depth knowledge of the suppliers’ networks and their level of reliability.”

“About five years ago, we started seeing a strong inversion of the business cycle, with the trend for integration running out of steam.”

“Business has picked up strongly for Walca,” underscores the manager, pointing out that demand exceeds supply for her company. But the demand has shifted towards higher-end watches, in line with the Swiss watch industry: “Our production consists mainly of automatic three-hand watches, GMT, chronographs, but we are also increasingly solicited for very high-end watches, tourbillons, perpetual calendars or the development of special modules. We clearly feel that the industry is declining in volume but increasing in average price.”

-

- The case manufacturer Fabhor (FM Swiss Logistics Group)

At Roventa-Henex, Jérôme Biard confirms this fundamental change: “Gone are the days when we carried out the entire production of big names of the watch industry. We are working on smaller series.” Today, the company counts around 40 customers with very diverse profiles. In 2018, Roventa-Henex led more than 100 different projects, i.e. two to three new projects per week. Many are startups, newcomers to the watch world.

New customers

Today, private label players must deal with a new variety of companies. The “big names” in the industry are still the core customer base when it comes to Swiss made production. Certain distributors and retailers, as well as non-watchmaking companies, also produce special series or labelled watches whose production is supplied to third parties.

Beyond these long-known profiles, a new category has taken off: that of watch start-ups, motivated by a reduced entry ticket to the watch industry and by the impact of crowdfunding platforms such as Kickstarter. Private label players are on the front line in receiving applications from those “dreamers”, as Jérôme Biard call them: entrepreneurs with limited finances but with plenty of ideas.

-

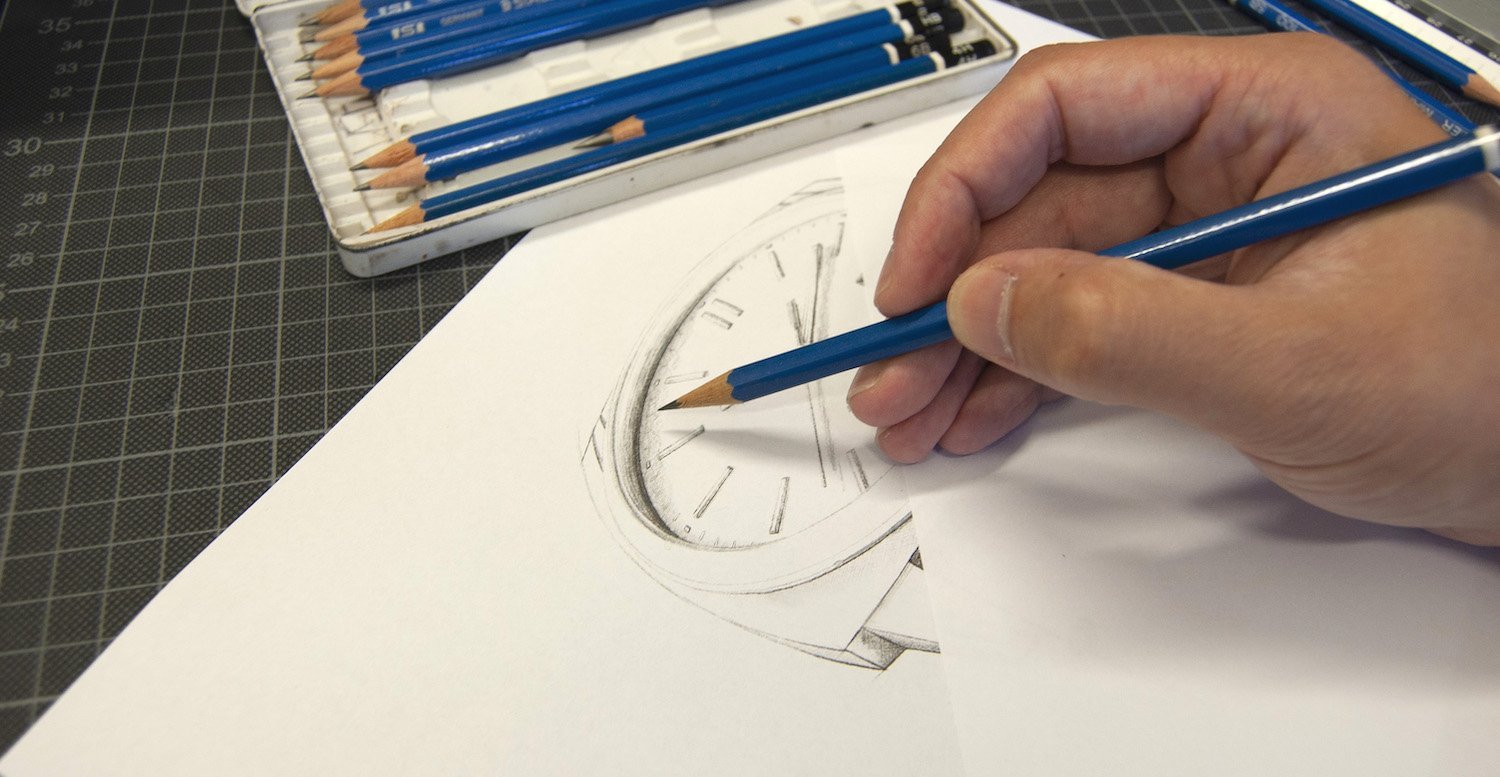

- In the workshops of Roventa-Henex

“They have to learn everything, because many have no prior experience in watchmaking,” the CEO of Roventa-Henex says. “We often spend a lot of time on operations that may run short. We go to the prototype stage; then the funding comes... or not”. At Walca, Christine Le Marquand also notices the numerous requests from these new players: W“hat we receive on our email address every day, it’s enormous... much more than ten years ago! And that requires a continuous follow-up.”

Without surprise, the big names in the watch industry (a number of which still claiming to be “manufactures”) refuse to disclose their partnerships with third parties. Meanwhile, startups are more transparent about it: Farer or Norqain are displaying on their website their collaboration with Roventa-Henex, same for Culem and Oak & Oscar with Walca.

“We’re also learning a lot from these new actors,” says Jérôme Biard. “A brand like Farer has been created by a genius of digital marketing. He’s a demanding customer, because he doesn’t come from the watch industry and doesn’t take for granted that there might be a three-day delay in delivery. This forces us to rethink our processes and speed up our time-to-market.”

Moving beyond production

The range of activities undertaken by private label players has also fundamentally widened. One of the companies at the forefront of this diversification is FM Swiss Logistics Group. Founded some 40 years ago as an assembler, it has evolved into an integrated manufacturing company that employs more than 200 people. Its main production site is in Mendrisio in Ticino. The company, which is still independent and in family hands, also has offices in Aargau for its marketing department and in Hong Kong for the Asian part of production.

-

- The headquarters of FM Swiss Logistics Group in Ticino

In addition to production, FM Swiss Logistics Group has expanded its range of services to include creation, design, R&D, production of cases and components, B2C logistics, after-sales service, marketing content and social networks. The private label world is thus getting closer to becoming licence specialists, such as Fossil Group or Movado Group.

-

- Guido Benedini, CEO of FM Swiss Logistics Group’s division in charge of private label, called Watchmakers

Guido Benedini, former CEO of Alpina, now manages Watchmakers, the unit of FM Swiss Logistics Group that draws on the resources of all the group’s companies (Fabhor, Timepieces, FM Swiss Logistics) to carry out private label projects.

“The private label business has completely changed,” he says. “It is now necessary to offer complete support throughout the client’s entire strategy, and not simply to coordinate an external supply chain. We offer “watches-as-a-service” instead of private label as it is traditionally understood.”

A number of new potential customers with very different profiles have appeared. “We have to handle a larger number of smaller projects,” Benedini sums up. “The only way for us to remain price-competitive and to keep reasonable margins is through the integration of new activities.”

FM Swiss Logistics Group’s annual production is several million units per year, ranging from affordable quartz watches made in Asia to high-end Swiss made mechanical timepieces. The bulk of the production ends up in a retail price range between 200 and 5,000 francs. The group has also started a connected watch segment and produced the smartwatch of Withings (a company which has since been taken over by Nokia).

“We just lived our best business years in the group’s history,” says Guido Benedini. “Our ambition now is to acquire new customers among big brands active in the fashion segment, direct-to-consumer newcomers, as well as traditional B2B brands that would not be able to finance an in-house production structure.”

Fluctuating Swiss made

A big question mark for many private label companies is to set up a presence in Asia or not. This decision fluctuates along the lines of the evolution of the Swiss made law, which has changed considerably during the last two decades - such that the recent coronavirus pandemic raises fears over the supply in Asian components. FM Swiss Logistics Group has opted to have production on both sides of the watch world. Guido Benedini points out: “In terms of volumes, a majority of our. watches are manufactured in Asia. But Swiss made is growing faster. The stronger the Swiss made regulation, the more value is created.”

Roventa-Henex and Walca have decided to concentrate solely on Swiss made production. “We receive an average of five requests a day from people who are interested in launching Swiss made brands,” says Jérôme Biard. “So we’re already busy. But we do have a presence in Hong Kong and we may be able to expand in Asia on the longer run with certain types of product.”

Uncertainties around ETA

At Walca, Christine Le Marquand confides that the transition to the new Swiss made standard has not been an easy one: “One of our major customers was so afraid of the new law that they decided to make a ‘Swiss movement’ production alongside their Swiss made timepieces.” She also notices that problems remain as far as the implementation of the new legislation is concerned: “Many Asian private label companies are keeping ‘business as usual’, only the assembly is done in Switzerland.”

One of the other big question marks for this segment is the supply of mechanical movements by ETA. It was thought that the matter would be settled by the end of 2019. But it hasn’t. The Swiss Competition Commission (Comco) has provisionally imposed on ETA to suspend its supplies to third parties (with a few exceptions), a decision which has been valid from 1 January 2020 and will apply at least until the summer, possibly until the end of the year.

“We also have a strong collaboration with Sellita. But we shouldn’t fall back on a new monopoly with them either.”

This issue has been going on in the industry for more than a decade, with countless twists and turns. SMEs are exempted from this provisional decision, according to the Comco communiqué: “ETA will be able to provide mechanical movements to SMEs on a voluntary basis. In the case of a delivery, however, all SMEs will have to be treated equally.” The FH denounced an “unclear” decision and Swatch Group a “diktat”.In January, Swatch Group took legal action to reverse the COMCO’s decision.

“It’s a hot topic because we still don’t know if we’ll be delivered,” says Jérôme Biard. “At the same time, we also have a strong collaboration with Sellita. But we shouldn’t fall back on a new monopoly with them either.” Guido Benedini insists on the importance of planning and securing supply towards his customers: “If deliveries are not consistent, everything can come to a standstill.”

Digital transforms the supply chain

Beyond Swiss made or ETA, one change might however have an even more profound impact on private label companies: the acceleration of time-to-market in the digital age and the shift from “mass-to-market” to “micro-manufacturing”. To take the pulse of these changes, we interviewed another private label specialist, Montrichard, a pioneer of “just-in-time” solutions based in Shenzhen in China - the global manufacturing centre for non-Swiss made watches. One of Montrichard’s most important customers is American fashion watch giant Timex.

Rémi Chabrat, the owner of Montrichard, started from two observations: the challenge of managing inventories as market upheavals are faster than ever (just watch the probably strong yet unknown real impact of the coronavirus pandemic); and the need to switch designs and products according to each market.

-

- Rémi Chabrat, CEO of Montrichard

“Partners can have their inventory compressed from eight months to eight weeks.”

Rémi Chabrat points out: “Ten years ago, we were receiving group orders for 1,000 pieces from our partners. Today, we are rather receiving 10 different orders of 50 pieces. In this new context, we need to be more flexible in the means of production, while more reactive in deliveries. A delicate equation!”

What’s the solution? “With the automation of orders, we associate the supply of components with micro-manufacturing,” says Chabrat. “We actually no longer manufacture watches that have not already been ordered. It is an inventory optimization solution. Doing so, a partner can see his stock levels compressed from 8 months to 8 weeks.”

-

- In the heart of inventory management at the Montrichard factory in Shenzhen (China)

Montrichard sells its “just-in-time” production management software (FINS) to third parties in a few cases (e.g. for Timex, which has a factory in the Philippines). Most of the time, the company takes over the entire production associated with the software, for about 20 customers at present, such as Triwa or TW Steel for example. The transition to the new system developed by Montrichard takes around a year to implement.

New challenges

As it stands, this system seems better suited to the affordable fashion watch segment and its high production volumes. However, brands in higher segment also face increasingly challenging logistics issues. As we’ve seen in many case, innovations that end up reaching the top of the range often start with the volume segment - just look at the development of e-commerce or the use of social networks, first initiated through new “low-cost” watch brands such as Daniel Wellington.

“The biggest challenges for the industry today are about reducing the inventories and optimising the cash flow,” says Rémi Chabrat. “The only solution is to transform stock into cash”. The issue of time-to-market is not unique to the watch industry. But this challenge will certainly keep private label companies hanging in uncertainties in the coming years, whatever their price range. The management of time (mastering short-term supply with long-term strategy) remains a critical issue in the industry of time!

Cover image: Fabhor (FM Swiss Logistics Group)