Can you imagine an international automobile show promoting cars as French? Most probably not. The French car, as a label, has little marketing value in the brand-driven automobile industry. In this sector, brands create the image of the products. Certainly, however, reference to national origin can be beneficial, as seen, for example, in the term, German Engineering, which remains a key selling point. The fact remains that, whether a client buys a Renault or an Audi, it is first and foremost the brand that he chooses, according to his budget.

On the other hand, let's have a look at the French watch shows. Here, the ‘France’ label serves more a business than an industry. In this case, the promotion is not so much on the quality of the brands, strictly speaking, as it is on the ‘French Touch’, a philosophy expected to appeal to customers, wholesalers, retailers and individuals.

Is this a bad thing? Some French watchmakers, such as Alain Silberstein, Richard Mille and Bernard Richards, the founder of BRM, think it is. However, one can make the opposite argument: the term ‘French Touch’ is to France what the label ‘Swiss Made’ is to Switzerland. The first is a mass-marketed approach, while the second involves a more product-specific strategy. To each his own methods, but Silberstein, Mille, and Richards do not subscribe to this herd mentality for French timekeeping.

Chanel, Alain Silberstein

Navigating against the mainstream

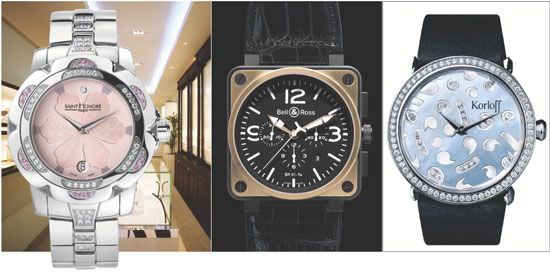

In France, there are still a few brands, like the three mentioned above, which are navigating against the mainstream. We might mention Bell & Ross, Korloff, Saint-Honoré Paris, Chanel, and Meyers International, and they are all doing rather well. Some have chosen to outsource production to the other side of the border, in order to take advantage of the valued ‘Swiss Made’ label. So, in these cases, are we really talking about French watchmaking? This seemingly naive question has been asked by Patrice Besnard, Délégué Général of the French Chamber of Watchmaking and Micro-Techniques (CFHM). Faced with competition from Asia in general and China in particular, Besnard urges a European approach to the watch industry, and a democratization of the term, ‘Swiss Made’.

At the head of the French watch trade shows is the CPDHBJO, the Professional Committee for the Development of the French Watch, Clock, Jewellery and Silverware industries. Each spring, the CPDHBJO publishes the financial reports for the previous year. They indicate that the watch industry, even though it holds an important position, does not perform as well as the jewellery industry. The Christian Bernard group, for example, which is working in both sectors, draws more profit from its jewellery activities than its watches. The French timepiece has now become more of a fashion accessory, and has moved quite a way from its timekeeping origins.

Saint Honoré, Bell & Ross and Korloff

The death throes of the French watch industry began in the 1980s

In opposition to this now widespread fashion accessory trend, the Frenchman, Richard Mille, produces Swiss Made watches in Breuleux, located in the Swiss canton of the Jura. Mille, himself, lives in Brittany, and once a week, he takes a flight to the Basel-Mulhouse airport, from where he then travels to his factory in Switzerland. His brand, which bears his name, has found an apparently bigger supporter for its production in the guise of the Federation of the Swiss watch industry (FH) than in his country’s own CFHM.

According to Mille, the beginning of the end of the French watch industry dates back to the 1980s, the decade of quartz par excellence. At this time, the Matra group, under the direction of Jean-Luc Lagardère, sold the brands Yema, Jazz, and Cupillard Rieme to the Japanese enterprise, Seiko. Along with this sale also went an entire compilation of French timekeeping savoir-faire. The secrets of micro-techniques, essential to the fabrication of component parts, thus left France for the land of the Rising Sun.

“From his side,” says Richard Mille, “Jean-Pierre Chevènement, a member of the Franche-Comté government and quasi Minister of the watch industry, took it upon himself to unify the commercial and industrial efforts of the French watch industry, by creating a special tax on every watch sold in France. While it seemed like a good idea at the time, the manufacturers of French component watch parts were quickly crushed by the Japanese competition.”

Today, this tax is collected by the CPDHBJO. As to the CFHM, this or-ganization defends the legal, commercial, and industrial interests of the French timekeeping industry in Europe and around the world. Membership in the CFHM, which is paid, is voluntary.

What was missing in France, according to Richard Mille, was a man of vision in the watch sector, “a genius.” On this point, Patrice Besnard of the CFHM, agrees. This genius, this man that France never had, “is Nicolas Hayek, the founder of the Swatch. Swiss watchmaking will be eternally grateful to him,” insists Richard Mille.

In France, watchmaking is perceived as a regional industry

Patrice Besnard recalls that, looking back to the past, the people involved in the timekeeping sector were not the same in the two neighbouring countries. “During the mid 1970s, there were 100,000 people working in the Swiss watch industry, as compared to 15,000 in France. Since then, the numbers have declined by threefold in both countries. In other words, France pulled through the watch crisis fairly well. Having said that, however, it is true that France has a Colbertist, interventionist view of the economy, which has imposed itself, and continues to impose itself in the watch industry.” With its interventionist attitude, the French government has undoubtedly lacked political acumen in dealing with its watchmakers. Perhaps, this is a sector that is not considered to be of capi-tal importance in the eyes of the politicians, unlike the automobile industry, for example. “Here in France, watchmaking is perceived as a regional industry,” adds Besnard woefully, “while in Switzerland, it is of national importance.”

“Not relying on public support”

Alain Silberstein is perhaps the only watchmaker, along with BRM, to produce haut de gamme watches with the ‘Made in France’ label. His workshops are located in Besançon, the seat of government in the Doubs department. Even though he is a member of the CFHM, he is quite vocal in his opposition to the French system for promoting the nation’s watches. Moreover, when his watches arrived on the market some 20 years ago, he was “lucky to be accepted by the FH,” he says, which welcomed him and included his watches in its booths at the foreign trade shows in Shanghai and Hong Kong. At that time, French watch manufacturers carried only quartz products made with com-ponent parts from the Far East. “I did not want to be mixed up with them,” says the fiery French creator.

“Watchmaking collectives serve absolutely no purpose,” he fulminates. “They are simply money wasted. The French industrials have COFACE, a public organization that covers the risks of exporting. Thus, for two years, we have a cushion, and that is very good. What is totally abnormal, on the other hand, is to see French brands, or those claiming to be such, which continue to be supported 20 years later by the special tax on watches. I believe that any self-respecting brand should not need to eternally rely on public aid to establish its credentials. To promote products made in the Far East with French public money is scandalous.”

“We are in a globalized economy”

Patrice Besnard does not appreciate this kind of talk. “People have to stop saying whatever they want,” he insists. “We live in a global economy. Competition on a price level is quite fierce. If some companies had not chosen to seek suppliers abroad, where would they be now?” The Délégué Général of the CFHM continues, “So, what then is a Swiss watch assembled by a French employee who comes across the border to work? When we purchase a Renault, we are indeed buying a French brand, but its component parts come from all over.” Patrice Besnard estimates that the French watch industry suffers from problems that are much more serious that the special watch tax. “Our handicaps are the following,” he says. “First, the State has neglected the past history of the French watch industry; secondly, the financial milieu is over cautious; and finally, there is the social structure of our country, where labour laws are not very favourable to employers and taxes on business are higher than in countries like Switzerland, for example.”

This may be the case, but in the opinion of Alain Silberstein, it would be better, in the immediate future, to change the strategies for marketing French watches. “It would be much nicer to support emerging small companies and strategic brand marketing efforts, rather than financing the large marketing houses, which set the trends,” emphatically adds the watchmaker from Besançon.

French or Swiss?

In the absence of an organization such as the CPDHBJO, how do French watch companies export their products? And, what does it mean to be ‘French’ in this sector? In fact, it seems that some brands are more ‘French’ than others. This is notably the case for Silberstein and BRM. Others, such as Chanel and Bell & Ross, move between France for their business management and Switzerland for their production. Bell & Ross’ Carlos Rosillo frankly admits that “for the client, watches made in La Chaux-de-Fonds by Bell & Ross, even though the brand is based in Paris, are not considered a priori French, but rather Swiss.”

“For the export of our products, we have distributors in other countries and a subsidiary in the United States,” explains Carlos Rosillo. Unlike Alain Silberstein, the owner of Bell & Ross does not condemn the special watch tax. “It doesn't bother me too much,” he says calmly. “I just hope that the funds collected are put to good use. We have an interest in it because we can have access to the statistics.”

Sophie Guyon, representing Korloff, based in Lyon, diplomatically states that her brand “is a willing member of the CPDHBJO, because we are all in the same profession.” Korloff watches are made in Bienne, Switzerland. “But, by our nature, we are a brand,” adds Sophie Guyon. “We therefore behave independently. While we respect the opinions of the CPDHBJO team, we do not participate in the trade shows that it organizes. We have always managed on our own.”

Nicolas Beaud, the International Director of Chanel watches, points out that his brand, as in the case of Richard Mille, has become associated with the Swiss FH “for manufacturing reasons,” rather than with the CPDHBJO, an organization that he is not too familiar with.

If all of these people are “in the same profession,” to repeat the words of Sophie Guyon, are they still, in reality, doing the same thing?

Source: Europa Star October-November 2006 Magazine Issue