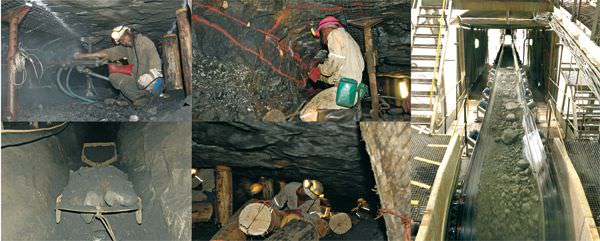

The brain tries to calm the heart as the elev-ator plummets the equivalent of 200 floors under the earth’s surface in a matter of seconds. 2,300 mineworkers make the same journey down this shaft every day, but that is hardly reassuring. As the gate crashes open on arrival, the air seems to be scarce. With temperatures hovering around the 29 degrees Centigrade mark (84 degrees Fahrenheit), humidity at an uncomfortable 80 percent and the smell of rotting wood and ammonia, the feeling of claustrophobia begins to mount.

This is no regular factory visit. With safety overalls, rubber boots, helmet and lamp, the journey into the mine is not for the weak or the fearful. The tunnels diminish in size as they spread out under the ground. Only the light from the miners’ helmets illuminates the way over an obstacle course of cables and machinery, through puddles and mud and down passageways that are sometimes only a metre in height. Suddenly the tunnels come to an abrupt end with a team of men drilling into the rock face in search of one of the world’s most precious metals – platinum.

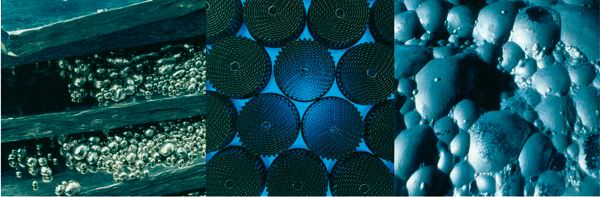

Platinum bars and grains, Flotation system, Catalytic converter

The mine

This is South Africa’s Impala mine, the second largest producer of platinum in the world, employing over 28,000 people. The vast majority of the employees work between 1,000 and 2,000 metres (3280 to 6560 feet) under the earth’s surface in a labyrinth of tunnels that cover over 65,000 square metres (700,000 square feet) of South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex.

Platinum formed here billions of years ago when molten rock, or lava, started to move upwards from the centre of the earth. Instead of erupting through the earth’s crust, the molten rock spread through the layers of the existing rock and cooled. As the heavy sulphides in the lava settled, two bands of plati-num formed, which are now known as the Merensky Reef (discovered by a German geologist, Hans Merensky in 1924) and the UG2 Reef.

There are 14 shafts covering the whole site. Each shaft leads to a myriad of tunnels, which are individually manned by teams of a dozen workers who physically mine the ore. These men (and women) work eight-hour shifts to install wooden support poles securing the ceiling of the tunnels. They then mark off the holes for the rock drill operators to pierce and blast the rock. Next it is the turn of the night shift who have the equally arduous task of cleaning out the blasted rock and bringing it to the surface.

Impala has mined 28 million tons of rock like this in the last 12 months. It seems a large number; it has to be, as it takes 14 tons of mined ore to obtain one ounce (28.3 grams) of pure platinum, or about 20 tons of rock to create just one Vacheron Constantin platinum watch. Add to this the fact that worldwide production of platinum is about 190 tons per annum, in comparison to gold, whose annual yield stands at approximately 3,300 tons, and it gets easier to appreciate the elevated price of platinum (At the time of print, prices were 1,660 Swiss Francs [US$1,431] per ounce for platinum and 928 Swiss Francs for gold [US$800]). In addition to this, there are no large inventories of platinum stored in central bank vaults, unlike gold, so any interruption in supply sends prices soaring.

The process

However, it is not only the scarcity of the earth’s reserves of platinum that has lead to today’s elevated price; over 50 different processes need to be executed before reaching the pure platinum stage. First of all, the rock is crushed to a powder and the minerals are extracted from the dirt by a system of flotation. Then, the ore is heated to lava, dried and mixed with dozens of different chemical agents to separate each element one by one. From the extraction of the ore to the final process can take over six weeks (See sidebar).

At the end of the production line, workers fill transparent plastic bags with the mustard yellow platinum salt that will then be turned into ingots or platinum grains according to the clients’ wishes. Daily platinum production amounts to an astonishing 150.8 million Swiss Francs (US$ 130 million) which better explains the presence of what looks like the whole of South Africa’s rugby team discretely watching every visitor like a hawk.

The lengthy and expensive production process is still only half the story behind plati-num’s value. Surprisingly, 70 percent of the world’s platinum goes to the automobile industry for the fabrication of catalytic converters. The increase in Europe’s diesel fleet and tighter emissions standards worldwide have both played a major role in pushing the price of platinum up over the last ten years. So has the growing Chinese market. Mr. Scott Stevenson from Impala’s refinery explained how, at Impala alone, China went from being a zero to a 500,000 ounce (14 metric tons) per year market from 1999 to 2004. The watch and jewellery industry only uses 20 percent of the world’s platinum, with the remaining ten percent being used in the production of products as diverse as, cancer drugs, pacemakers, ladders, fishing rods, parachute silk, fertilisers, i-pods, and even the glue in Post-it notes!

The price of a platinum timepiece increases further due to the cost of machining platinum components – cases, crowns, dials etc. A plati-num watch case, for example, can take up to three times longer to produce than a gold one. This is predominantly due to the need for specially manufactured tools to turn, mill and drill the components. Slower tool speeds and lower pressures are also needed to minimize friction of the tools as well as successive hand-polishing processes to create the characteristic platinum finish.

Extracting platinum from the rock

The concentrator

The first stage of turning the mined rock into platinum takes place above ground at a plant called the concentrator. The concentrator eliminates 95 percent of the unwanted rock by crushing it into a fine powder using huge mills and steel balls. The crushed ore is then mixed with water and special agents that make the metal particles hydrophobic. Air is then pumped through the liquid creating bubbles to which the metal particles adhere (copper, nickel, platinum, palladium, ruthenium, rhodium, gold and silver). These float to the surface and are recuperated.

The smelter

After being dried, the concentrate is transported to the smelter where it is heated in a furnace at temperatures of over 1,000 degrees centigrade. During this process the last unwanted minerals are eliminated and the remaining matte is transferred to converters, where air is blown through it to remove the iron and sulphur. The granules are then weighed and sent to the Springs refinery in Johannesburg in a high security convoy that is tracked by satellite.

The refineries

The Springs refineries are divided into two sections: the Base Metals Refinery and the Precious Metals Refinery. The Base Metals Refinery removes the copper, nickel and cobalt and the Precious Metals Refinery separates the platinum, palladium, gold, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium, osmium, and silver. Using different chemical processes, each metal is extracted one by one. It takes 14 days at the refinery before the platinum salt is completely extracted. The platinum comes out as a bright yellow powder before being made into ingots or granules.

The appeal of platinum watches

For 2006, the Swiss Watch Federation reported an increase of 23 percent for plati-num watch sales (+17.2 percent in 2005), with a sales volume of more than 390 million Swiss Francs. (US$ 330 million). Compare these figures to the overall Swiss watch exports in 2006, at an increase of 10.9 percent on the previous year, at 13 billion Swiss Francs, and it is clear that platinum watches are an ever more popular choice.

So what is the appeal? When only a trained eye can tell a platinum watch from a white gold model, (Patek Philippe put a diamond on theirs to avoid confusion) why are today’s clients willing to pay so much more for platinum? The watch industry is seeing a trend towards the use of products that are rare and expensive - fossils, meteorites, precious stones and so forth. Platinum fits into this rarity category especially as very few companies launch large series of timepieces in platinum, amplifying the exclusivity of a platinum watch. However, the purchase of a platinum watch is not just a question of having something rare and expensive.

Firstly, platinum is far purer than gold. Impala produces platinum that is 99.95 percent pure. In comparison, 18-carat gold is usually 75 percent pure. Gold is a naturally soft metal, it is for this reason that it is almost never produced in its purest, 24-carat, form. It needs to be mixed with other elements to increase its strength and durability. Rose gold is usually combined with copper, while white gold is mixed with nickel and/or silver to add strength and colour. Platinum, on the other hand, is purer and therefore resistant to tarnishing, unlike white gold, which can take on a yellowish tinge over the years. This purity is a major selling point, especially in markets like Japan, where purity is considered a significant quality.

In addition to this, platinum’s durability is far superior to that of gold. “Platinum is the perfect choice for a lifetime of wear - its density and weight make it more durable than other metals. For example, if a platinum piece is scratched, the metal is merely displaced and none of its volume is lost, so it remains what it always was - a symbol of all things eternal,” explains, Juan-Carlos Torres, CEO Vacheron Constantin. Platinum is also resist-ant to heat and acids and is hypoallergenic as it has fewer alloys than gold. Its mass is quite incredible, a six-inch (15 centimetre) cube of platinum, for example, weighs about the same as the average man!

After five fascinating days with Vacheron Constantin, following the journey of platinum from the depths of the earth to the presentation of the latest timepieces, the appreciation of this precious metal takes on new meaning. From the mines to the huge chemical refineries, it is enthralling to see the work that goes into creating just one single ounce of platinum. In the creation of a work of art, the journey is often as intriguing as the finished product, and in the case of the platinum watch, this is most definitely true.

MALTE TOURBILLON REGULATOR, MALTE PERPETUAL CALENDAR CHRONOGRAPH

Vacheron Constantin’s Collection Excellence Platine

Vacheron Constantin started producing plati-num as early as the 1820s. Last year the company launched its ‘Vacheron Constantin Collection Excellence Platine,’ a very limited collector’s edition destined for exclusive distribution, each model being produced with a solid platinum dial (marked with the Pt950 stamp), case and buckle. Production of platinum timepieces has been on the rise at Vacheron Constantin with a 76 percent increase in production for 2006-2007 in comparison to 2004-2005. Juan-Carlos Torres explains why the company decided to increase its platinum collections, “In 2006, Vacheron Constantin had entered a new quarter of a century of watchmaking tradition. As we have embarked on the journey ahead, what finer symbol could there be to capture the values we hold dear and aspirations for the future than 950 platinum in all its purity, exclusivity and eternity?"

2007 sees the launch of two new pieces for the Collection Excellence Platine: a Malte Tourbillon Regulator and a Malte Perpetual Calendar Chronograph, both in limited editions of 50 individually numbered pieces. The Malte Tourbillon Regular is equipped with Vacheron Constantin’s 11790R calibre, a mechanical hand-wound movement. The timepiece is distinguished by a regulator-type hour and minute display, along with a small seconds hand on the tourbillon and a power-reserve of over 40 hours. The Malte Perpetual Calendar Chronograph is equipped with the 1141 QPR calibre, also a mechanical hand-wound movement, which is notable for its column-wheel chronograph mechanism with 30-minute counter at 3 o’clock, central chronograph seconds hand, a perpetual calendar and a moon phase display.

It is hard to believe that these timepieces started their life billions of years ago under the ground. It has been a long journey, but one that surfaces into a work of art that reveals the true splendour of this pure and understated metal.

Photo credit: Morvan Alain and Platinum Today

Source: Europa Star December-Januar 2008 Magazine Issue