The ascension of BNB Concept, which has grown from four people at its creation in May 2004 to 187 employees in January 2009, seems nearly unbelievable. Yet it is perfectly explainable by a series of factors that came together, both external and internal.

On the external side, the very favourable situation of the watch industry strongly supported this growth. As you remember, between 2004 and 2008, the value of Swiss watch exports increased from 11 billion CHF to about 18 billion CHF. The main part of this growth was due to the increase in highly sophisticated mechanical watches. This category is precisely the target of BNB, a pioneer in exceptional tourbillons, new materials, and the integration of the mechanics into the casing.

The amazing growth of BNB cannot, however, be explained solely by these external factors. The primary reasons lie elsewhere. One is timing: the brand was able to offer ingenious and creative solutions at a time when many new emerging players were entering the haut de gamme sector. Another factor involves the organization of the manufacture itself—an organization that is, as we will see, completely atypical.

Tax exemption and reinvestment

BNB was created in 2004 by three men whose initials gave rise to its name—Mathias Buttet, Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini. Today, the enterprise is headed by Mathias Buttet, the other two founders having left the company in 2007. That same year, Buttet formed a partnership with the French investors, EPF Partners, who retain a minority share of BNB but who do not have a seat on the Board of Directors.

According to Buttet, “they will realize their investment within six years.” There is a strong possibility that, at this date, BNB will go public. “Our accounting is already up to standards,” he adds.

Mathias Buttet, however, “doesn’t like to make predictions” when it comes to future shareholders. He is the principal owner, and he is also an employee of the company since all the profits are recycled back into growing the business. And grow, it has. Since taking its first steps, BNB has seen a growth rate of 200 percent per year, “including to the end of 2008”. It also enjoys a tax-exempt status for ten years on condition that no dividends will be dispersed to the shareholders. Thus, the company operates with its cash flow, which is generated by the mandatory payment of one third of the price when a piece is ordered.

Workshop

28 clients

One of the great strengths of BNB is its portfolio of clients—28 as of today. That said, we know that watchmakers are very sensitive to confidentiality. Only eight of their clients will openly admit their association. “But things are changing little by little,” states Buttet, and people are beginning to ask me for permission to place the term, by BNB, on their products.”

Among the watchmakers that are proudly and publicly declaring their collaboration with BNB are Romain Jérôme, Concord, Franc Vila, Hublot, HD3, Wyler, and Bell & Ross (for its carbon tourbillon). Clearly, this list is made up primarily of brands that offer a new form of timekeeping, one that is expressly exploratory, even sometimes experimental, in a break with the aesthetic canons of traditional watchmaking.

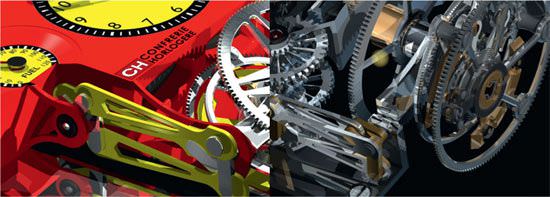

Yet, a common BNB style exists in a sort of sculptural or architectural affirmation of the movement. More precisely, it is a form of “fusion” (the word popularized by Jean-Claude Biver doesn’t belong to him alone) between the case and the movement. This leads some to say that BNB, while a constructor and manufacturer, is also a designer in its own way.

Verticalization nearly achieved

BNB’s new “fusion” approach to timekeeping would not be possible without the unusual organizational structure of its facilities. Today divided over five sites, the enterprise is nearing complete verticalization, which means that it would, in time, be able to design and produce 100 percent of the components for its movements and cases.

From conception and construction to the integral production of all the movement parts—including the balance spring and barrel spring, without forgetting electroplating, decoration, and encasing, as well as the case, dial, and hands—BNB wants to master the entire chain of watch production.

Of the company’s nearly 200 employees, 94 are watchmakers, with a handful working in the Vallée de Joux. “This verticalization is an entrepreneur’s obligation,” affirms the enthusiastic and passionately independent Buttet. (As a former employee at Franck Muller, he saw first hand the progressive verticalization of that group.) “I do not want to depend on others,” he continues. “It is also a question of social responsibility. I create jobs and I don’t want anyone from anywhere deciding, one day, for reasons that don’t concern me, to throw us all out with the bathwater.”

BNB Tourbillon Répétition Minute Movement

Confidence in the youth

One might think that the concern for “social responsibility” is merely rhetoric. But this is not the case. You only need visit the manufacture to see for yourself that this affirmation goes way beyond a simple idea, but that it has been applied directly in a very original and effective manner.

The first thing we noticed is that the average age is very young—only 27 years old. “Anyone can establish a factory and put in the machines. But what about the people? My management style is rather particular,” insists Mathias Buttet. “I hire them right out of school, and very importantly, I trust them. If they mess up, they mess up. It’s not a big thing. That’s the way it is and I understand that. I teach them responsibility. At BNB, everyone does everything from A to Z. The watchmakers, for example, receive their kit and completely assemble their watch. The same thing for the mechanics. Each is responsible for his or her CNC. Each person prepares their own tools, calculates the dimensions, and runs their own machine.”

Buttet goes on to explain, “This method of working involves higher costs perhaps than having the tasks divided up—although that still remains to be seen—but this way, we have traceability for each product and higher quality. If a product is returned after it is sold, we know who made it. Therefore the person in question can learn his weak points and work to improve them. We also have an in-house training centre that is permanent and continuous, offering training aimed precisely at the needs of each employee.”

Flexible hours

Another feature of this particular type of organization is that the employees are free to set their own hours. BNB is open 24 hours a day, including nights and weekends. Each employee decides what hours he or she wants to work, while understanding that deadlines or a certain rhythm must be respected in order to complete the expected work (for example, so many pieces must be produced a month, or the fact that a particular task will take a total of 25 hours). Only one person has fixed hours at BNB, and that is the cook.

There are many advantages to this system. If someone wants to take a day off and go skiing, not a problem. In exchange, they can come to work on a rainy Sunday. A single mother, for example, who would have to work only 60 percent time somewhere else could work 100 percent at BNB by arranging her work schedule to fit her time constraints. Other advantages are less stress, better ambiance, heightened responsibility, and greater motivation. In the same spirit, all managers are employees first, and all promotions come from the inside, as this favours the emergence of a natural authority rather than a fixed hierarchy.

There is also a sense of working together at BNB. For example, in the R & D department, each constructor works in tandem and in close proximity with a prototype maker. This way each step of the piece’s creation can be continu-ously validated. This close cooperation is one of the secrets of BNB’s rapidity in developing a project. A project that would normally take several years elsewhere can be done in three to nine months at BNB.

Sharing knowledge

Another important feature is that the watch ateliers are organized into “villages”, as Buttet calls them. “Given the number of our clients, the flow at BNB is not easy to manage. There are small quantities and lots of different component parts. Each specific order must therefore be assigned to a specific ‘village’ that is made up of four or five people, one of whom is more experienced and can teach the others.”

“Once the order has been completed, each person changes ‘villages’ and thus changes teams. In the end, this results in a true sharing of understanding and the level of savoir-faire rises naturally. Knowledge is shared because, if there is one thing I detest, it is holding back information. Knowledge is there to be spread around, to circulate freely. I am even considering to no longer patent our discoveries.”

Far from being anecdotal, this unusual type of organization is at the heart of the innovative creativity that BNB brings to contemporary timekeeping. Because of its youth, its reactivity, and its spirit of competition, BNB has succeeded in breaking a number of taboos, in crossing boundaries, and going beyond the barriers that often destroy creativity.

The architecture of the buildings has also been well thought out. It was not designed by an outsider, concerned mostly about offering a corporate image, but rather designed in great detail as a function of the flow, the specific organization, and the requirements of the production.

Two axis tourbillon for the Confrérie Horlogère

Members of the Confrérie Horlogère year 2008-2009

From left: David Rodriguez, Sabitry Montandon, Brigitte Carneiro, Clara Bise, Gabriel Salgado de Arce, Ken Kosiyama, Ranieri Ilicher.

Watchmaking brotherhood

One of the strongest and most emblematic examples of the originality and particularity of BNB is certainly the recent launch of the Watchmaking Brotherhood (Confrérie Horlogère). Seven of the company’s best watchmakers and artisans (including three women) were chosen to become members of this group. Under this title, each has the opportunity to create his or her own watch, in total freedom and with access to all the technical resources of the manufacture. Each of these watches, which are meant to be innovative and bold, will be produced in ten pieces and guaranteed for life (which no one has dared do up to now).

But the journey does not stop there since the Brotherhood intends to be, above all, an incubator for future brands. Depending on whatever successes can be had, the idea is that each member of the group can launch his or her own brand that will then become an entity totally independent of BNB.

This is a veritable technical and human adventure as exemplified by one of the first pieces, created by David Rodriguez. With its claws and its bridges seemingly broken and then repaired, this timepiece testifies to the harsh destiny of a young Peruvian orphan— abandoned and mistreated—who found refuge in Switzerland, and redemption in watchmaking.

The crisis?

How does Buttet put the “crisis” that the watch industry fears so much into perspective? “It is an opportunity,” he asserts. “The crisis mostly affects watches selling for between 3,000 and 20,000 francs, whose sales have been hard hit. On the other hand, the very haut de gamme, which is our daily bread, continues to sell. The decrease in volume will allow us to stabilize our processes. And, we will take advantage of the time to more deeply develop our R & D in all domains—mechanical, material, functionalities, and design. We will come out of this even stronger.”

Source: Europa Star February-March 2009 Magazine Issue