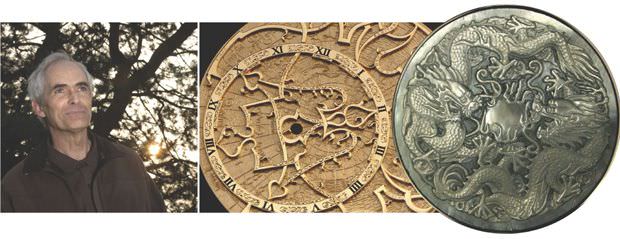

Established as an independent engraver in 1978, Olivier Vaucher (he was born in 1954) has, as he admits, had many difficult years, and has known many ups and downs. But he never gave in to the temptation to give it all up or to find refuge in stone setting, as have so many others. Standing firm during the watch crisis that dragged on and on, he managed to hold on, and then saw his tenacity rewarded starting about ten years ago with the renewed interest in engraving.

Astrolabe for Corum, DRAGONS for Alain Silberstein

Watchmaking roots

Perhaps Olivier’s determination to succeed came from his watchmaking roots. Hailing originally from Fleurier, the Vaucher family has been in watchmaking for more than 300 years! His father was a watchmaker, who worked at the Fontainemelon Watch Factory (later purchased by ETA), where he created calibres, year after year, which would, in the middle of the darkest years of the industry, never see the light of day. Olivier hesitated about following in his father’s footsteps. The watch industry was collapsing and seemed to be in its final desperate throes. So, the young man dabbled a bit in horticulture before attending the school of applied arts in La Chaux-de-Fonds, where he learned the art of engraving.

In 1974, he found himself in Geneva, engraving blocks of steel in the printing industry. Later he joined Blum & Züllig, “the best engraving atelier in Geneva,” he says, where he “learned all the secrets of the craft.” But Olivier Vaucher has a fiercely independent spirit and, in 1978, he set up his own workshop, with the original slogan that continues today: informer la matière, or in English, ‘investigating materials’.

Today, his atelier, located in a surprising island of calm only a few steps from one of the busiest streets in Geneva, employs about a dozen people within its centuries-old walls. Most have been with Vaucher for a decade or more, and have complementary skills in engraving, animal art, and miniature painting.

Finally, after much turmoil, the beginning of the 1990s saw the rebirth of the watch industry. Swiss timekeeping again started making exceptional pieces for collectors. “In fact,” explains Vaucher, “Audemars Piguet was my first major client. The company had just re-launched the trend for finely decorated skeleton movements, and this got us back in the saddle again, so to speak. Before that, the fashion was for large gadroons and elongated links on bracelets, which involved a whole other technique, one that was physical but not very interesting from the point of view of our skills.”

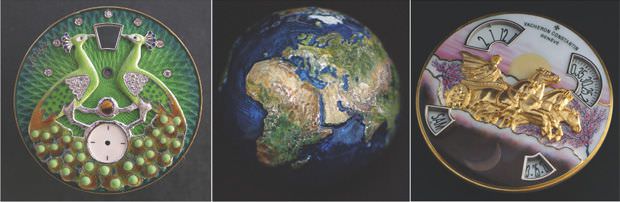

PAON for Corum , PLANETARIUM for Richard Mille, APOLLO’S CHARIOT for Vacheron Constantin

Restoring the craft

In 1992, Audemars Piguet ordered additional elaborate pieces, based on the ‘Four Seasons’ theme and then on prestigious classic auto-mobiles, all requiring engraving on the dial and case. These pieces allowed the creativity and savoir-faire of Vaucher’s atelier to progress, and the métier was gradually restored.

Richard Daners, master watchmaker at Gübelin, then asked Vaucher for a delicate engraving of the ‘jack’ automatons with raised hands. Orders started coming in one after the other. In 1997, Corum ordered rather complex pieces, such as the watch whose dial was engraved with an image of the Coliseum, its movement covered in Roman friezes, and its oscillating weight carved to represent Romulus and Rémus in bas-relief. Later came a limited series dear to the heart of Séverin Wunderman: cocks fighting, peacocks, bats, and a crimson Lucifer on black diamonds. Other brands came calling as well. Ulysse Nardin ordered a series of various ‘jack’ watches with varied themes, such as the bell ringers of Saint Mark’s Square and Genghis Khan. Alain Silberstein had Vaucher’s atelier make high fire enamelled cloisonné dragons and mother-of-pearl snakes in relief.

LES MASQUES for Vacheron Constantin – the main work steps

The pinnacle of the masks

Without a doubt, the work with Vacheron Constantin would let Olivier Vaucher and his team skilfully demonstrate the full extent of their talents. Vaucher himself is inquisitive by nature, and has always sought to mix the most traditional techniques with the most advanced modern methods. After having realized for Vacheron Constantin, in 1995, cloisonné and high fire enamelled dials in naturalistic themes, then in 2005, exceptional pieces, including the Four Seasons with Apollo’s chariot carved in relief on high fire enamel, in honour of the 250th anniversary of the Geneva manufacture, a pinnacle was reached with the creation of the remarkable collection of ‘Masques.’

This collection (which Europa Star presented in detail in issue 3.07) gave Olivier Vaucher the opportunity to demonstrate all his creativity, to allow him to “combine everything possible relating to engraving and to surpass what has been done in the past.” To be able to bring an amazing realism to the miniature reproductions of the masks found in Geneva’s Barbier-Müller museum, Vaucher and his team had to employ all sorts of different techniques, from the most advanced to the most… alchemistic.

Each mask was scanned in three dimensions in order to find the ideal angle for positioning it on the dial, and then a rough engraving was made with a laser. From here, the hand of the skilled engraver took over: adding the subtle relief work, the high and low points, smoothing the rough edges, reproducing the effects caused by centuries of time. Crafted in gold, the masks were then treated to perfectly reflect the colour and material of the original (polychrome wood, or gilded bronze, natural strands of hair). Along the way, Vaucher and his team were transformed into alchemists, reconstituting the lab-oratory of an ancient chemist, using chemical stills, and researching ancient formulas for chemical and galvanic treatments.

The most striking example of their research is the reproduction of the green and grey spots on the Chinese funerary mask, dating back to the Liao dynasty (907 – 1125). Since gold does not oxidize, Vaucher and his team had to resort to an unusual process: the spots were created by depositing small blotches of copper onto the gold that were then oxidized. This is only one example of the ingenious treasures created by Vaucher, yet it is emblematic of what this veritable artistic acrobat loves above all: “To travel to unknown shores, to try to push back the frontiers as far as possible of the ancient art of engraving.”

The delightful animated fairies and other precious dials for Van Cleef & Arpels, Pont arriere du double tourbillon for Breguet

A great year

The year 2007 will be particularly good for Vaucher, who, in addition to the Masques made for Vacheron Constantin, has participated in another series of remarkable pieces: the delightful animated fairies on the guilloché and high fire enamelled dials made for Van Cleef & Arpels. He also signed a series of dials for tourbillons for the same brand, including a peacock in cloisonné and high fire enamelled relief and a mosaic in relief made of sparkles of mother-of-pearl coming from around the world.

Another remarkable realization this year is the grand relief engraving showing great perspective, representing a multitude of planets, which adorns the back of a rotating double tourbillon signed by Breguet.

Olivier Vaucher’s tenacity and determination are finally being justly rewarded as watchmaking renews its ties with the great decor-ative arts that have marked its history. This is undoubtedly the veritable and most authentic form of watchmaking ‘glamour’.

Source: Europa Star October-November 2007 Magazine Issue