here’s a word that Sebastian Vivas, Heritage & Museum Director at Audemars Piguet, likes to repeat often: “oxymoron”. An oxymoron is a rhetorical device that combines opposites, as its name indicates: from the Greek oxus, “sharp”, and môros, “dull”. By juxtaposing antithetical terms, the speaker hopes to suggest a strong and surprising image.

The new Audemars Piguet Workshop Museum is an oxymoron. It combines the solid and traditional original building of 1868 with a futuristic-looking spiral of metal and glass. But this is not just an architect’s fantasy. This architectural oxymoron “creates a strong and surprising image” that corresponds closely to the very nature of Audemars Piguet, a brand strongly rooted in the watchmaking tradition of the Vallée de Joux, one of the cradles of complications, but capable of decisive breakthroughs, as demonstrated in particular by the Royal Oak which, in the early 1970s, shocked and surprised, before becoming the watchmaking icon that we know today.

Designed by BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), the studio that won the architectural competition, the spiral of the Atelier Museum complements both the original building from 1868 and the brand’s headquarters, built in 1907 and extended several times since then. The premises have become an identifying symbol of Audemars Piguet, as well as being its main gateway for the public. To access the Atelier Museum, you must pass through this iconic building.

In the beginning was iron

After passing through a roomy reception area, visitors are welcomed at the entrance to the spiral by... a piece of iron. It comes from a very old mine in the extensive Risoud forest, which overlooks the Vallée de Joux. Everything in this region began with iron and metallurgy. Without the presence of iron, watchmaking would probably never have developed in this remote place with its hostile environment.

A relief model shows in detail the geographical location of the valley in French-speaking Switzerland, and the chemin des horlogers or watchmakers’ path that once linked it to Geneva. From there, watches were dispatched out into the wider world, descending by sledge to the shores of Lake Geneva in winter. Then the model comes to life, turns on itself and reveals the Joux Valley in greater detail.

This geography, and the iron that came out of this land, represent a timely reminder that watchmaking is not an above-ground art; that the conditions of its birth and development are closely linked to specific places and their particular characteristics.

Nevertheless, geography isn’t the only thing that matters – there’s also the people, the inhabitants of this land. The strength and legitimacy of the watchmaking industry is rooted in its long history, and that history is built on the transmission of knowledge and its deepening from one generation to the next.

This is brought home by an imposing installation in the form of a metal tree-like structure, from which are hung hundreds of small plaques detailing the successive generations of the great watchmaking families of the Valley. The installation, based on genealogical research, helps the visitor to understand how watchmaking developed over the centuries to achieve the form it has today.

-

- The family tree of the Vallée de Joux families

Family at the core

Among the families of the Valley, we find of course the Audemars and Piguet lines, to whom, immediately after the family tree, homage is paid through the exceptional pieces that have punctuated their history. It starts with the oldest piece in the Vallée de Joux, a “master watch” by Joseph Piguet, dated 1769, more than a century before the Le Brassus workshop opened its doors in 1875.

-

- This pocket watch, presented at the beginning of the visit, is currently the oldest watch on display in the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet. It was made by Joseph Piguet in 1769 to mark the end of his apprenticeship and his entry into the Corporation des Horlogers de la Vallée de Joux, and has remained in the family ever since. It now belongs to Olivier Audemars, Joseph Piguet’s great-great-great-grandson.

The importance of families and watchmaking dynasties is all the more central as, in those heroic times, the craftsmen of the Valley worked together, in a dense “network”, as we would say today. This system was known as “établissage”. And we can thus affirm that Audemars Piguet was an authentic product of this dense network of interconnected skills that irrigated the Vallée de Joux.

There are breathtaking pieces by Louis Audemars, an accomplished specialist in complications, who produced movements and watches for Breguet, Oudin and Leroy, the great watchmakers of the time.

Another outstanding figure is Louis-Elisée Piguet (1836-1924), a specialist in Grandes Sonneries, whose masterpiece, the Universelle, is displayed in the spiral. As an aside, many readers might be surprised to learn that, until the 1950s, Audemars Piguet (officially founded in 1875 by Jules Louis Audemars and Edward Auguste Piguet), produced almost exclusively unique pieces.

The art of the escapement

A gentle slope takes you gradually through the spiral, whose fluid course is delimited by generous curved windows that reveal the entire space while guiding the path through this luminous and transparent structure.

-

- The journey inside the spiral and the original Audemars Piguet building

This is not simply a succession of rooms, but thematically dedicated sections that open up organically, one into another. Each of these sections is introduced by an animated sculptural and didactic element with which the visitor can interact.

After having admired the foundational masterpieces of the past, the chapter on the technique that made them possible takes centre stage. This section is introduced by an imposing automaton created by François Junod, one of the great masters of this mechanical science, to which he has brought a whimsical element of fantasy and humour. The sculpture, in the form of an animated and interactive anatomical model of movement, introduces the visitor to the mechanical mysteries of energy and its regulation.

The regulation of energy, the keystone of the art of watchmaking, is also explained to visitors through concrete examples illustrating how it has evolved. Its history can be traced from the first verge escapements to the contemporary double skeleton balance, by way of Robin, cylinder, Swiss anchor, trigger, ultra-flat tourbillon and direct drive escapements...

All of which enables the visitor to approach the next section, dedicated to the various complications, with a better understanding.

At the heart of the company and of the museum

Each of the following sections details the intricacies of time measurement using examples from watches produced by Audemars Piguet over the course of its history.

It begins with calendar watches, introduced by a demonstration that explains the “inaccuracies” of the different calendars: normal, annual and perpetual. The theme is illustrated by perpetual calendar pocket watches, from the first wristwatch with a complete calendar (day, date, month), the first perpetual calendar wristwatch with leap year indication (1955), to the Royal Oak Selfwinding Perpetual Calendar Ultra-Thin which, with its 2.89 mm thick movement and 6.3 mm high case, is the thinnest automatic perpetual calendar wristwatch in the world.

-

- The Royal Oak Selfwinding Perpetual Calendar Ultra-Thin

Another section is dedicated to striking watches. Visitors first learn how to transform the measurement of hours, quarter-hours and minutes into sounds thanks to another demonstration. All they have to do is strike a gong in rhythm to indicate time acoustically. This apparently simple exercise turns out to be more complex than it first appears.

After this practical exercise, they can admire the many achievements of this delicate art that draws upon acoustics and mechanical science. Among these are tiny ladies’ repeaters in a multitude of shapes, from pendants and brooches to wristwatches.

This is followed by a section devoted to chronographs, also introduced by a demonstration that gives a glimpse of the complexity of these mechanisms designed to measure short periods of time. Today the chronograph seems a relatively banal creation in the eyes of many, however it is important to grasp the complexity that makes it so challenging to master completely. The history of the chronograph is that of gradual conquest, made up of a series of incremental improvements and refinements of its mechanisms.

Audemars Piguet produced very few chronographs prior to the 1980s (precisely 307 wristwatches before that date, but that does not include the many pocket watches because, unlike in wristwatches, variations in complications had dominated since the 19th century). From that time, many increasingly sophisticated models were produced. One of the most successful contemporary examples to be found in the museum is the Royal Oak Concept Laptimer Michael Schumacher, released in 2015.

-

- The Royal Oak Concept Laptimer Michael Schumacher is the world’s first mechanical chronograph with an alternating consecutive lap timing system with flyback function, designed and engineered specifically to measure continuous lap times on the motor racing circuit. The push-piece at nine o’clock stops one of the two chronograph hands and simultaneously resets the other to zero and restarts it. Thus, the timing of the next lap begins even before the previous time has been recorded, and the watch makes it possible to dispense with the system of two or more chronographs, simplifying the process by using a single wrist chronograph. The watch can also retain a specific reference time: simply stop one hand with the push-piece at nine o’clock and then use the flyback push-piece at four o’clock to reset the other hand to zero and start timing a new lap. Finally, the watch can be used as a classic flyback chronograph by operating the two hands simultaneously.

A century of Grandes Complications

A contemplative – and equally interactive – walk takes you to the Grandes Complications area. As a reminder of the astronomical cycles at the origin of the history of watchmaking, timepieces with complications are presented in spherical showcases inspired by the solar system. At the centre of the spiral is the most complex watch ever made by Audemars Piguet, the Universelle by Louis-Elisée Piguet.

This timepiece, one of the most complex of its time with its 21 complications, was finalised by Audemars Piguet in 1889 based on a sketch by Louis-Elisée Piguet, then delivered to Union Glashütte in Dresden, which completed the decoration and casing-up before marketing it under its name in 1901. The timepiece’s movement comprises 1,168 components and displays a perpetual calendar, minute repeater with chime, large and small striking mechanism, split-seconds chronograph, 1/5th of a second flywheel with reset system, deadbeat seconds and minute alarm mechanism.

-

- L’Universelle by Louis-Elisée Piguet, front

-

- L’Universelle by Louis-Elisée Piguet, back

Seven pocket watches and a wristwatch revolve around this star of the museum, all of which display the same functions: perpetual calendar, minute repeater, split-seconds chronograph, moon phase and small seconds. These watches, all dating from 1882 to 1996, are the result of the hard work of successive generations of watchmakers, collectively labouring at their workbenches for more than a century; perfecting, miniaturising and assembling the countless components that must all interact to display the greatest possible number of time measurements, mechanically and simultaneously.

-

- Grande Complication, estimated production date 1882. Watch sold in 1885.

-

- Large Complication Calibre 18SMCRV. Movement manufactured in 1912. Watch sold to Gübelin in 1922.

-

- Jules Audemars 25984 Grande Complication in rose gold. 1996

“Finally, here it is...”

“Finally, here it is, after two months of torment and my head and eyes damaged. I won’t do it again for any price!”

November 19, 1921

Meylan Grosjean

This is an excerpt from a note written in 1921 by the watchmaker who had just finished assembling the world’s smallest 5-minute repeater watch, with a diameter of 15.8 mm!

Watchmaking is all about miniaturisation. The race to be as small as possible is introduced by… a telescope. The strategy works perfectly and helps us to grasp immediately, by contemplating a tiny component at the other end of the lens, the dizzy intensity of working in such reduced dimensions.

The same applies to the exploration of the extra-flat domain – the watchmaker’s dream of accommodating the highest possible number of components in the slenderest possible space. The example shown is the self-winding Perpetual Calendar of 1978, then the thinnest in the world, equipped with a movement (2120/2800) 3.95 mm thick, which the manufacture delivered at the height of the quartz crisis.

-

- Automatic Perpetual Calendar of 1978

The workshops in the spiral

Housed in one arm of the spiral that gives directly onto the open landscape of the Valley — a natural environment that seems totally unspoilt, almost as it was in past centuries – craftsmen and watchmakers work in the museum.

Unlike many other similar examples, these workshops inside the museum are not demonstration spaces but real workspaces where watchmakers work on decoration, engraving, setting or Grandes Complications.

It is in the heart of the museum that today’s Grandes Complications are assembled, adjusted and refined. Here, the best watchmakers go about their business, sometimes working for months on the same piece (it takes 6 to 8 months of assembly, adjustment and setting for a single piece). “Meticulous” is too weak a word for this art, because every grand complication is first assembled, observed in operation, then completely disassembled and readjusted, before being finally reassembled.

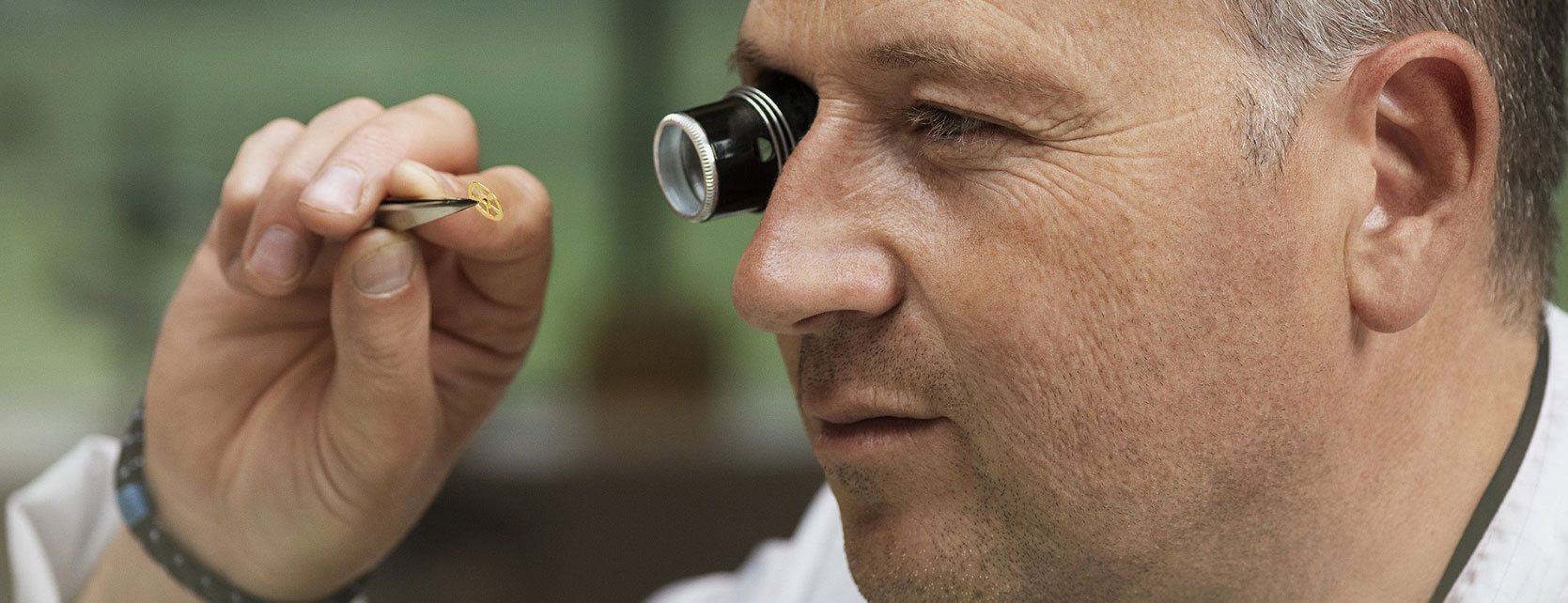

Getting your hands dirty

As they walk through the spiral, visitors can also sit at a workbench and learn a few key procedures. With the “Cyclops” screwed into one eye (wedging this small watchmaker’s loupe securely into the eye socket is an achievement in itself...), visitors can take a first step in this micro-universe, and try their hand at circular graining, a form of decoration, or simply screwing in a component. It’s a way to experience the patience, concentration, meticulousness and precision of the movements necessary merely to insert a tiny screw into its housing and tighten it without leaving any scratches.

If they raise their heads from the bench to take a breather, visitors can meditate on the landscape that opens up in front of him. The Valley seems untouched, the natural environment similar to how it was in centuries past. But how far this remote and still wild place has come!

From here, some of the most complex small mechanical timepieces ever made have spread out around the world. From here, local and then international networks were created over the decades, enabling the complex watchmaking industry to expand across the continents.

And in return, the major artistic and aesthetic trends of distant continents have reached this remote place, their fashions transforming the very shape of the watch.

And it is here, in this peaceful and rugged valley, that some of the most striking formal revolutions in watchmaking emerged.

The saga of the Royal Oak

Is this the ultimate “oxymoron” that the spiral tour has in store for us?

On exiting, visitors are faced with a series of black monoliths that open to reveal an impressive collection of Royal Oak watches.

Born in 1972, the Royal Oak, “the first luxury steel watch”, has enjoyed exceptionally good fortune. Designed by the famous watch designer Gérald Genta, the Royal Oak ushered in a stylistic revolution to the art of horology. Over the course of its few decades of existence, it has come in all shapes and materials, opening up many new avenues (as demonstrated by the Offshore and Concept versions) and at the same time rejuvenating traditional watchmaking.

The Royal Oak, like the Atelier Museum itself, is also an oxymoron. Stemming from a centuries-old watchmaking tradition, it nevertheless marks a break with that tradition, and heralds the introduction of uncompromising modernity.

Moreover, it is undoubtedly thanks to the worldwide success of the Royal Oak that Audemars Piguet has successfully “verticalised” its production, by gradually integrating all the horological professions and thus guaranteeing the preservation of its most precious legacy: its independence and its family-owned identity.

This is one of the most important lessons to be learned from this Museum, which is both a piece of heritage and a vibrant, living space. It’s a lesson that its innovative architecture forcefully brings home.

![Audemars Piguet [RE]Master02: an archive beauty returns](local/cache-gd2/ae/db0d917660691e6e2b418090f0af56.jpg?1739457435)