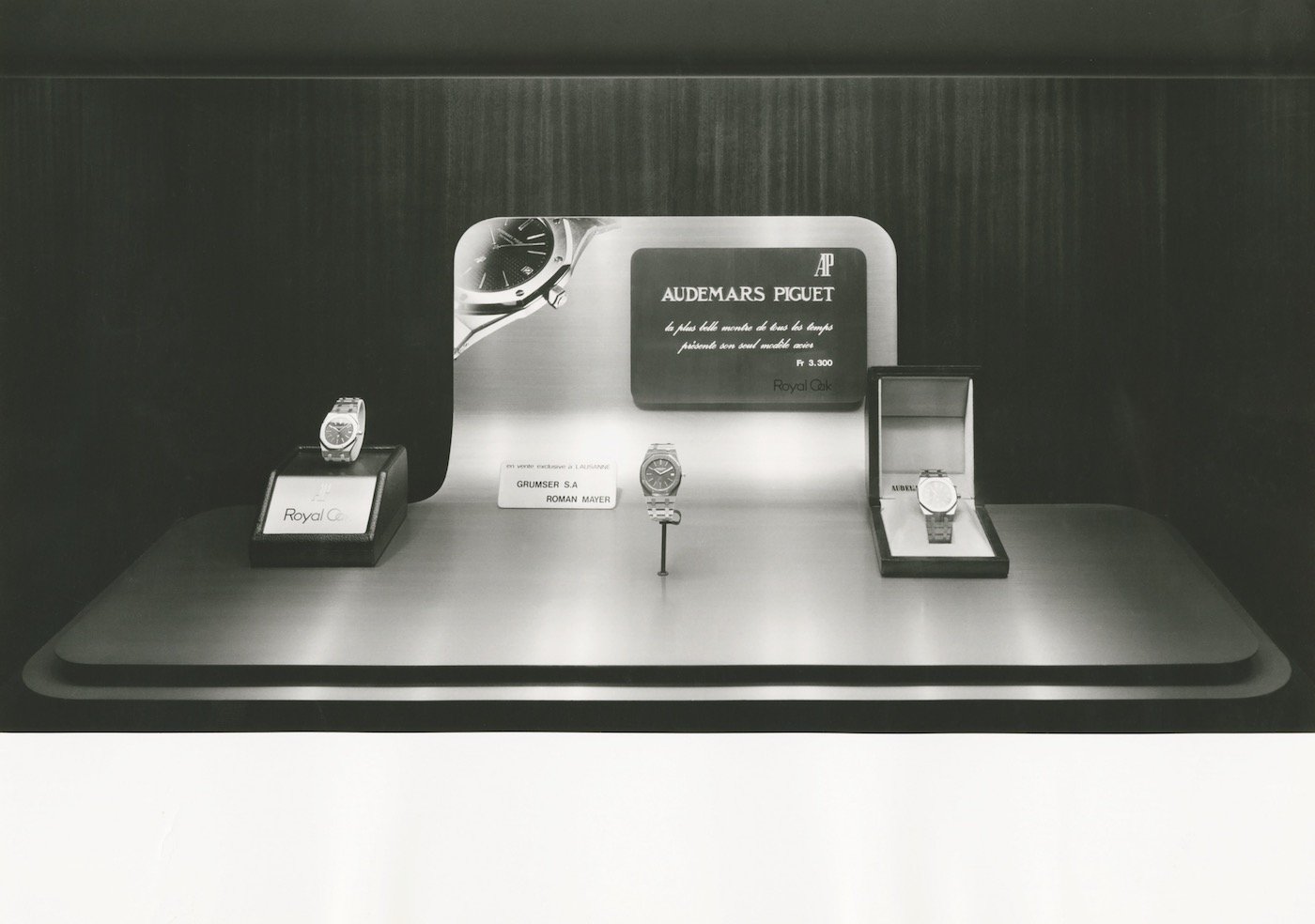

ifty years ago the Royal Oak, first shown in public at the 1972 Basel Fair, was born. The undeniable success ever since of this watch, which was designed by Gérald Genta on the initiative of Audemars Piguet and revolutionised watchmaking by imposing new stylistic codes, is well known.

Much less is known about what actually nestles inside the costliest steel case of its time. Concealed beneath the octagonal bezel and its famous visible screws (seen as a sacrilege at the time) is an exceptional movement: the ultra-thin, automatic Calibre 2120 and its variant with date indication, the 2121. A calibre that first saw the light of day in 1967, five years before the Royal Oak, and was then manufactured and honed for more than 50 years.

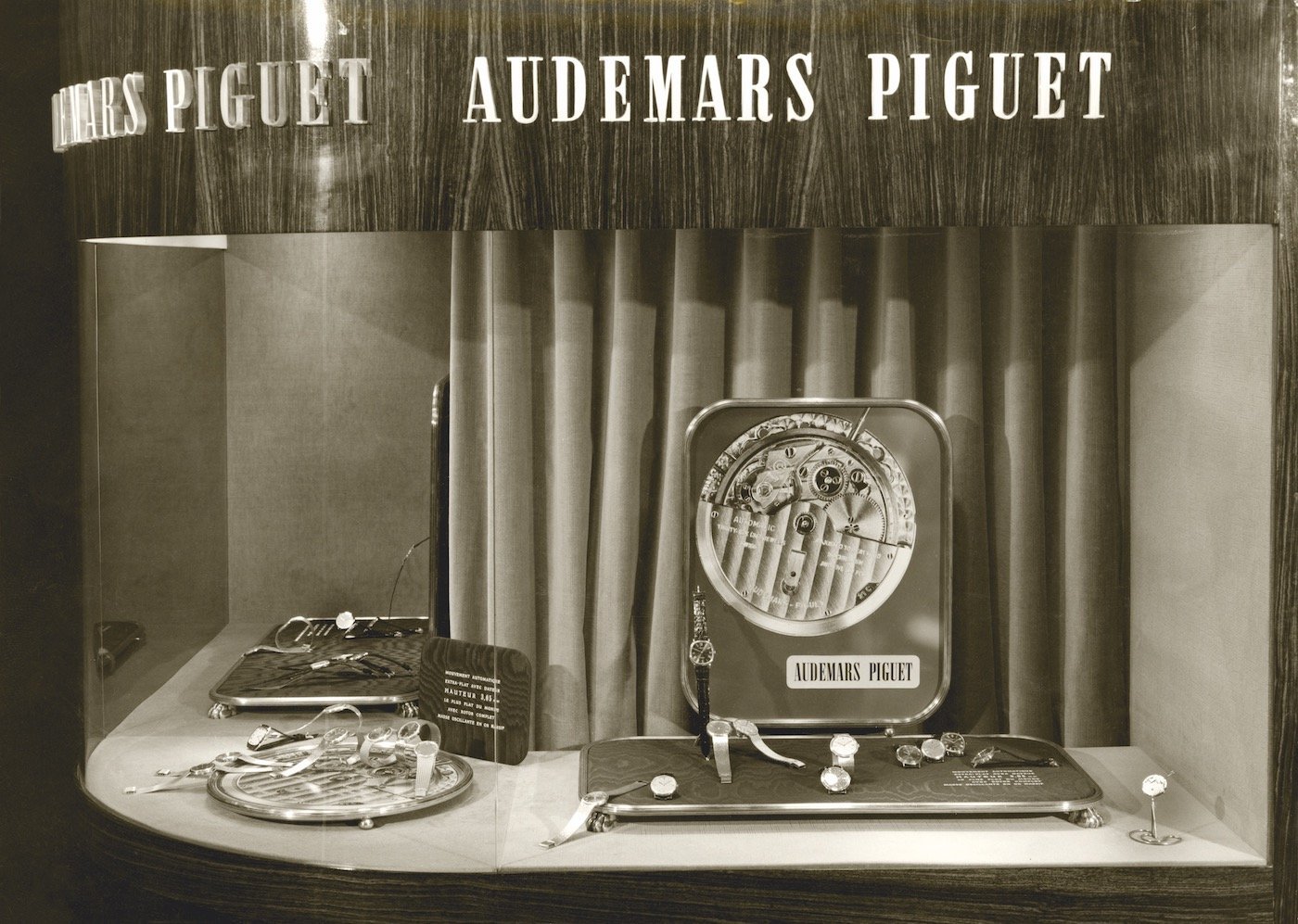

It was Calibre 2120 that made possible the creation of the Royal Oak Jumbo, a self-winding but ultra-thin watch – a feat of ingenuity at the time. Certainly, thin and ultra-thin watches had already been around for a long time; they were even a speciality of Audemars Piguet between 1900 and 1910 and significantly developed after the Second World War.

-

- Thin is beautiful. An advertisement for the Calibre 2003 ultra-thin watch from 1958 in the Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie

In 1958, as company historians explain, “more than three-quarters of Audemars Piguet watches were equipped with the manual Calibre 2003, barely 1.64mm thick". But adding an automatic winding system with its rotor (which provides more energy the heavier it is) while remaining within the thin or ultra-thin range meant having to solve a very tricky equation. Impossible, even, according to some. Yet it was worth a try: ultra-thinness combined with an automatic movement would be the horological holy grail, a combination that the modern, chic and sporty customers of the 1960s were sure to adopt.

The result of natural collaboration

To achieve it, the manufactures and établisseurs worked hand in hand, something that came quite naturally to them. It should be pointed out that this was the eve of the 1960s and it was happening in the Joux Valley, a bucolic and isolated watchmaking hotspot, where everyone was either related or knew one another. Friendship and solidarity were strong. There, on the one hand, was Audemars Piguet, a family business then headed up by Jacques-Louis Audemars, the grandson of one of the brand’s two founders, and on the other Jaeger-LeCoultre, then a family-owned company under the umbrella of the SAPIC Group (Société Anonyme des Participations Industrielles et Commerciales, which also owned Vacheron Constantin), and whose chief designer was a brilliant watchmaking engineer who had already invented several self-win ing systems – Maurice Audemars.

Since time immemorial, the watchmaking ecosystem in the valley had been based on établissage. Établisseurs, of which Audemars Piguet was one example, assemble parts, do the adjustment and finishing work and add the case. The parts came from a “myriad of highly specialised workshops: from the small cottage-industry cadraturier [who did the under-dial work] to the large-scale manufacturer of ébauches”, like Jaeger-LeCoultre, who in the valley was nicknamed “la Grande Maison” – the big company.

Audemars Piguet had maintained close ties with LeCoultre & Cie (later Jaeger-LeCoultre) since the 19th century and these grew even stronger after 1948. Moreover, Vacheron Constantin, with the prestige of its two centuries of existence, was a faithful customer of Audemars Piguet. Just by way of an anecdote, “it was a certain Francis Berger, Vacheron Constantin’s sales director, who went on to sell the first Royal Oak in white gold to the Shah of Iran in 1972,” explains Sébastien Vivas and his team of historians and archivists at Audemars Piguet.

Besides those three players, Patek Philippe was also involved in the design of the Calibre 2120 which, after the Royal Oak, also powered the first Nautilus from 1976, then the Overseas by Vacheron Constantin from 1977.

Those were the days. Today, such a criss-cross of collaboration and in-depth exchanges between watch companies, factories and craftworkers is unimaginable. At a time of concentration, vertical integration and marketing requirements, glib communications and financial pressure, it is simply unthinkable. Who, today, would even think of performing such “music for four hands”, as the historians at Audemars Piguet describe it?

A piano piece for four hands

Patiently, and carefully avoiding glib phrases but instead supporting their demonstration with facts, documents and archival evidence, the historians at AP have reconstituted the whole story of the creation of this exceptional movement. It really is like deciphering the notes of a piano piece for four hands.

Audemars Piguet introduced its first automatic watches in 1954 using 6.65mm-thick LeCoultre ébauches. So not exactly thin. But there was increasing pressure to create a thin self-winding calibre. This is attested by a letter from Audemars Piguet to LeCoultre in 1958: “Customer demand is chiefly for thin watches (...) As competition is getting tougher all the time, we need to keep an eye on the thickness of our products”. The “competition” was mainly Piaget, which in 1960 introduced its automatic Calibre 12P, just 2.3mm thick. But that feat was made possible by the integration of a micro-rotor, to which Audemars Piguet preferred a central rotor, “a more efficient, but infinitely more difficult option”.

After several false starts, including a project launched in 1960 together with Frédéric Piguet but never completed, then various attempts that were either unsuccessful or too difficult to adjust, the project really took off in 1963. Development was based on the famous Calibre 2003 (ébauche Jaeger-LeCoultre 803), designed by Maurice Audemars in 1953, 1.64 mm thick. This was where it all began.

“All the characteristics of the movement were adapted, the height, frequency, power reserve,” we are told. Jacques-Louis Audemars wore a prototype on his wrist as early as June 1964. The plans were drawn up in 1966 and the first calibres delivered in 1967.

A continual exchange went on between Audemars Piguet and LeCoultre. The two Audemars, Jacques-Louis of Audemars Piguet, and Maurice, of LeCoultre & Cie. discussed everything: questions of winding, springs, power reserve, height, balance, etc. Vacheron Constantin was also involved in the development and, to a lesser degree, Patek Philippe too, it would seem.

An exceptional calibre

The result fulfilled all expectations. Just 2.45mm thick in all, in 1967 Calibre 2120 became the world’s thinnest self-winding calibre with a central rotor, a record that remained unbroken for decades.

Its chief innovation (patent number CH14338/65) lay in its self-winding system which, with its 28mm rotor diameter and heavy oscillating weight, delivered superior performance to that of the micro-rotor. But in an ultra-thin mechanism, these characteristics can make the system more fragile, especially in the event of a shock. But Calibre 2120 offered a simple solution: at its edges, the rotor ran on ruby bearings. These bearings turned a little like the wheels of a train on a rail. This circular rail is, moreover, one of the most easily recognisable visual components of this calibre.

-

- One of the original plans: that of the rotor of Calibre 2120

To ensure greater thinness, the movement had no seconds hand. It beat at a frequency of 19,800 vibrations an hour and had an anti-shock system made by Kif Parechocs, a company also based in the Joux Valley. The winding system was bidirectional, which meant that the mechanism could be wound regardless of the direction of rotation of the rotor.

Circular graining, straight graining, chamfering and bevelling, polishing, Geneva stripes, gilding, snailing, buffing – its decoration satisfied the highest standards.

At the birth of the Royal Oak

Since it was first issued in 1967, Calibre 2120 and its date indicating variant, Calibre 2121, have evolved and been continuously improved throughout their 55 years of existence (for more details, see the article History of Calibres 2120 and 2121).

Calibre 2120 can boast of being at the heart of two major developments at Audemars Piguet. The first, of course, is the creation of the Royal Oak in 1972. Without this automatic movement just 2.45mm thick, the fate of the Royal Oak would have been very different. The Jumbo might never have seen the light of day, or at least not as we know it, being both ultra-thin (around 7.15mm thick overall) and with what was, for the time, a very large diameter – 39mm. That said, the diameter itself was a constraint resulting both from the dimensions of Calibre 2121 (28mm) and from the innovative architecture of its visual design, with its hexagonal screws starting from the bezel and traversing the entire monobloc case and oversized hermetic seal.

-

- The original Calibre 2120 of 1967

It’s a very fine example of form follows function, as the architectural expression goes, which is the key to any major design. And, as it turned out, it would go on to pioneer the “sport-chic” watch segment.

Renaissance of skeletonisation

But at the other end of the spectrum, Calibre 2120 would also foster the revival of a much more traditional art long practised at Audemars Piguet (especially in the 1930s and 1950s) but dormant since then: openworking.

The handsome and innovative Calibre 2120 provided the opportunity to rediscover this somewhat forgotten craft. Georges Golay, the visionary head of Audemars Piguet who had just launched the most modern watch of the time, decided to reserve a batch of 100 movements for skeletonisation. But in the workshops, few people still mastered the delicate technique of making mechanical lace. A few young watchmakers set about it, assisted by some of the older ones.

-

- Advertisement in Italian for both the Royal Oak and the art of skeletonisation. Italy played an important role in the growing fascination with the Royal Oak.

Knowing that it takes a skilled craftworker 150 hours to complete one part, you can imagine the size of the task. But three years later, the 100 watches were finished. In 1978, 300 new Calibre 2120s were reserved for openworking, which was introduced into the Royal Oak collection starting in 1986.

For the next stage, the 20th anniversary of the Royal Oak in 1992, Audemars Piguet presented a Jumbo model with a sapphire crystal caseback revealing a perfectly finished, decorated movement. Back in the early 1990s, sapphire crystal casebacks were still a rarity. It was an instant success. And sapphire crystal casebacks gradually became an established feature. Calibre 2120 and Calibre 2121 continued to evolve during the 2000s and beyond, with, notably, a variety of skeletonised oscillating weights, bevelled, faceted and decorated with arabesques.

From watch assembler to watchmaker

But Calibre 2120 was to do Audemars Piguet another crucial favour: it contributed to its final transformation into a vertically integrated watchmaker.

By the late 1990s, the 2120 powered only the Jumbo models, of which fewer and fewer were produced. The whole watchmaking landscape was being reshaped, groups were forming and Richemont, having bought Vacheron Constantin, also acquired Jaeger-LeCoultre. At the same period, that manufacture announced that it would no longer be producing blanks for the 2120.

What seemed to be a bitter blow was, in fact, “almost an opportunity”. At the time, vertical integration was a key concern at Audemars Piguet that had already led the company to produce its own calibre, the 3090, in 1999. Taking back control of every stage of production of the Calibre 2120 helped accelerate a process that was already under way, and today is fully complete.

The year 2022 marks the 55th anniversary of faithful service, as the saying goes, by Calibre 2120 and its derivative 2121. They are finally bowing out altogether to make way for the new generation: Calibre 7121. But that is another story, which is only just beginning.

Read the full story of Calibre 2120: https://apchronicles.audemarspiguet.com/en/article/calibres-2120-2121

![Audemars Piguet [RE]Master02: an archive beauty returns](local/cache-gd2/ae/db0d917660691e6e2b418090f0af56.jpg?1739457435)