o design a perpetual calendar timepiece is one of horology’s highest ideals. That is because, as the name suggests, the aim is to put into mechanical form the great celestial clock that governs the march of time unperturbed. What finer achievement could there be for a watchmaker than to create a mechanism that can measure and display with unerring precision, and without outside intervention, the time of day and the weeks, months, and years by means of a mechanical set of gear trains? Did not the French philosopher Voltaire believe, as a Deist, that God himself was the “Great Clockmaker”?

Today, most of us live according to the divisions of the year established by the Gregorian calendar. It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 to more closely mimic the solar clock. Protestant nations reluctant to follow the Pope’s innovation were said “to disagree with the sun,” choosing to follow the pre-existing Julian calendar, which had, up until that point, accumulated approximately 11 days’ delay (roughly one day per century) compared to the solar clock.

So in 1582, when the Gregorian calendar came into effect for those nations choosing to adopt it, October 4 was immediately followed by October 15 to correct the delay. Since then, our Gregorian calendar has come closer to solar precision, but to remain accurate, there are still leap years for it to juggle, with a day added to February every four years but removed at the turn of the century (except once every four hundred years). This certainly gives the watchmaker something to get their teeth into, transforming the astronomical calculations into a play of mechanical forces.

The art of the perpetual calendar timepiece, first mastered around the end of the eighteenth century, is something that Patek Philippe has long excelled at. Numerous pocket watches made by the manufacture provide eloquent proof. The company was even the proud parent of the world’s first perpetual calendar wristwatch, which was made in 1925.

Deceptively simple, fiendishly complex

The clarity and legibility of the perpetual calendar’s time and calendar indications are essential qualities. And these elements are often combined with moon phases to complete the picture. Over the years Patek Philippe has presented a range of displays: with hands on subsidiary dials (models endowed with the calibre 240 Q); or a double aperture for the day and the month, with a subsidiary dial for a date hand paired with a moon-phase aperture (models featuring the calibre 324 S Q); or yet again, with the date displayed by a retrograde hand and the day and month by apertures (this goes for models fitted with the calibre 324 S QR).

Another form of display exists too, but only in a handful of pocket watches. Until now, it had never been used for a wristwatch. This type of display presents a single linear aperture for the day, date, and month, positioned at twelve o’clock. One particular example – the Ref. 725/4, a pocket watch from 1972 held in the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva – caught the eye of the manufacture’s engineers and inspired the new Perpetual Calendar Ref. 5236.

The calendar information on the museum piece’s dial is arranged in-line at twelve o’clock above a moon-phase aperture framed by a subsidiary seconds scale. This in-line layout expresses both geometrically and graphically the essence of a fine perpetual calendar from a horological viewpoint, displaying precise, uncluttered, complete information that is clear at a glance. But as the engineers would discover, accommodating such a calendar display in a wristwatch raises many technical challenges.

Four discs

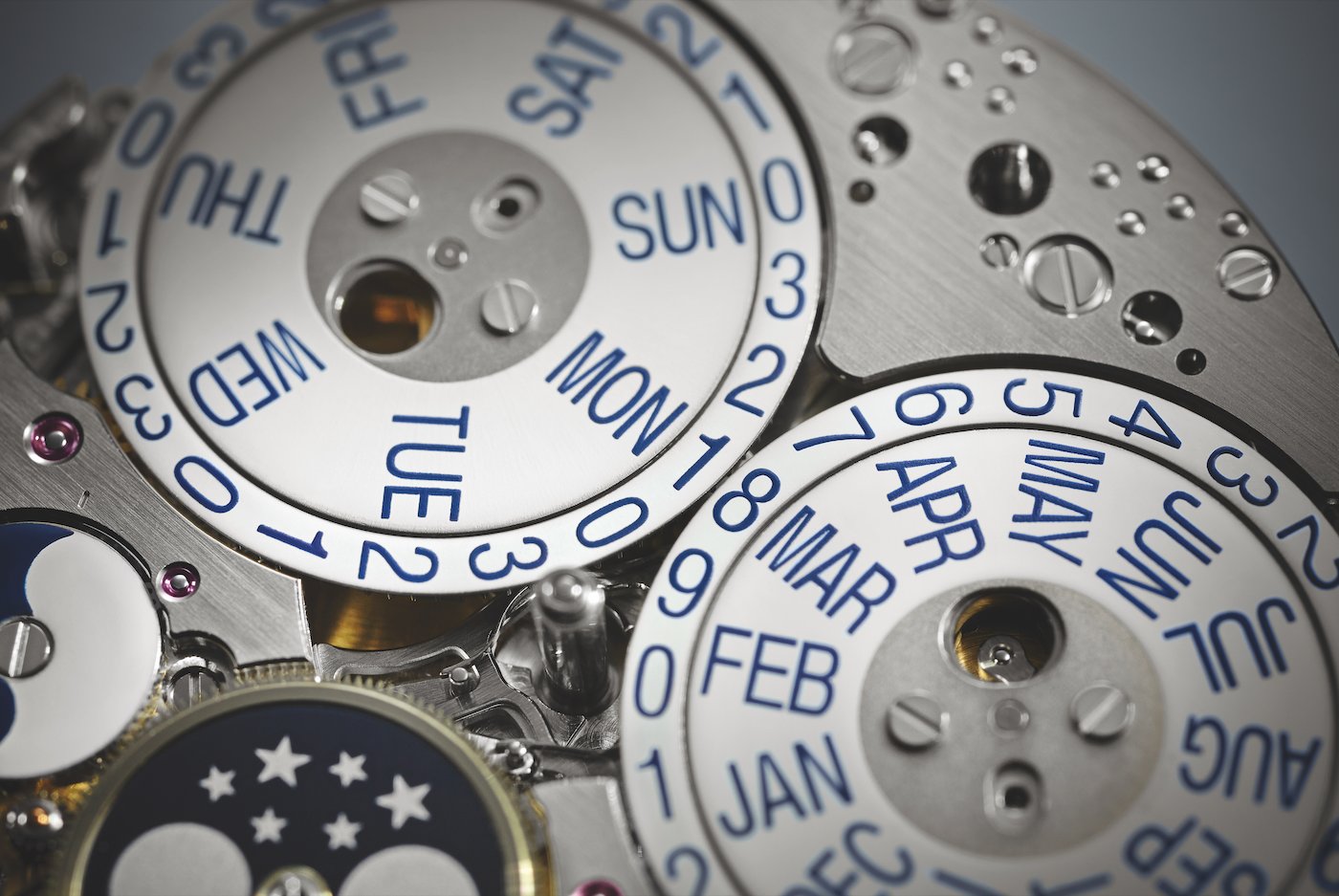

As stated earlier, legibility is the grail of this little cosmological machine, the perpetual calendar. To achieve optimum clarity despite the minimal space in terms of diameter and thickness available in a wristwatch, the engineers developed an innovative system of four separate discs, one each for the month and the day and two for the date (one for the tens and the other for the units). The aim was to make the numbers and other indications as large as possible while maximising the system’s long-term reliability in compliance with the stipulations of the Patek Philippe Seal.

To limit the total thickness of the calibre, the perpetual calendar mechanism was integrated as a separate module mounted on a specially designed plate. With its four discs, this device alone required 118 more components than a classic perpetual calendar display system. And to ensure that all the information appeared on the same plane with no overlap, Patek Philippe’s engineers and watchmakers developed a display system comprising two tiny double ball bearings with coplanar balls, for which they have filed a patent application.

Two additional applications were filed for the perpet- ual calendar mechanism. One concerns a device for executing the date changeover from the thirty-first to the first. That device allows the unit (the number 1) to remain in place during the transition from the thirty-first of the month to the first of the following month by means of a cleverly contrived date star, two of whose 31 teeth have been removed. The other patent relates to a shock-absorber mechanism that reinforces the security of the date display and the perfect synchronisation between its two discs. It prevents any accidental jump in the event of a shock or during a correction.

These are far from being minor considerations, since if the units were to move out of step with the tens, the only solution would be to take the watch back to its makers. Executed using a dragging display rather than an instantaneous jump, these calendar indications (day, date, and month in that order) are complemented by two small round apertures, one for the leap-year cycle (positioned at four o’clock) and the other for a day/night indicator (at eight o’clock). Both are very useful when adjusting the calendar, which is done easily using the three correctors set into the side of the case. A fourth corrector relates to the moon phases, displayed with extreme precision in an aperture at the centre of the subsidiary seconds dial at six o’clock.

Energy optimisation

This calendar module is powered by the new calibre 31-260 PS QL (QL for in-line perpetual calendar), based on the previous calibre (31-260 REG QA) launched in 2011 in the Annual Calendar Regulator Ref. 5235. The new self-winding movement’s recessed mini-rotor contributes to its slender finesse. But for this movement to be able to drive a perpetual calendar, which is energy-hungry by nature, the design had to incorporate a number of Patek Philippe’s most recent technical innovations. The engineers increased the barrel torque by 20 per cent and boosted the winding power of the mini-rotor by making the rotor out of platinum, which has a greater mass than the 22K gold used previously. Another contributor to this energy optimisation was the use of jewel bearings in the gear trains driving the calendar discs.

Furthermore, along with a Spiromax® balance spring made from Silinvar®, the new calibre 31-260 PS QL is equipped with a reduction wheel that lessens wear by disconnecting the self-winding mechanism when the manual-winding mode is active – an innovation that was patented by Patek Philippe in 2019.

Finally, this splendid movement also acquired a new look, with two distinctive bridges for the escapement and sweep-seconds hand. While this layout complicates life for the watchmaker, it treats watch enthusiasts to an uninterrupted view of the architecture and its lavishly finished components, which are visible through the protective sapphire crystal caseback.

For a perpetual calendar, only timeless beauty will do

For a perpetual calendar, only timeless beauty will do. That principle radiates from the dial and the case of the new Ref. 5236P. A chamfered, polished bezel frames the blue lacquered dial. And, as is customary in order to distinguish Patek Philippe’s platinum wristwatches, the caseband features a diamond set at six o’clock. The three in-line perpetual calendar displays, in blue on a white ground, stand out to perfection, while the large railway-track minute scale and the subsidiary seconds scale at six o’clock (framing the ultra-precise moon-phase display) lend an appropriately technical touch, accentuated by white gold baton-style hands and hour markers.

Streamlined architecture, an uncluttered dial, and an understated 41.3 mm platinum case with perfectly balanced proportions all complement a timepiece that is destined to measure calendar time unperturbed for years, decades, and centuries. This truly is a watch equipped for perpetuity.