ithout the suppliers, their expertise and know-how, often maintained and developed over generations, the Swiss watch industry of today would be very different. Without this fertile seedbed, would it be as dominant as it is today? Perhaps not.

These sub-contractors not only supply the big names with components, materials, technology and services; they are also the veins and arteries of the great watchmaking body, and its most active laboratory. A physical, brick-and- mortar laboratory maintained by people very different, in most cases, from the emissaries of the big watch names from whom their orders come.

Without this fertile seedbed, would the Swiss watch industry be as dominant as it is today? Perhaps not.

And therein lies a paradox. All the suppliers we met have in common a kind of in-built independence. They are more rugged by far than the watchmaking elite (their domain is the workbench, not the desk), they are ignorant of any “storytelling” and direct in their manner of speaking (while being perfectly capable of keeping secrets, and leaving you in no doubt about that fact). But all of them will immediately captivate you with the depth of their arcane knowledge. They have strong personalities. (A friend, also a supplier, qualifies them and himself as “bears of the Jura”).

Yet their independence, whether they work alone, in workshops, or at the helm of medium-sized or large organisations, depends closely on the whims of their customers, about which they can do little.

The watch suppliers are a reminder that the watchmaking industry did not grow from nothing. It was born of and is rooted in a shared territory, and there the adventure continues to unfold. But today, it is continuing in a fog of uncertainty. Visibility is scarcely more than three or four months ahead. Instead of production programmes that span a year, orders are spluttering in, adding more uncertainty to an already precarious situation.

Depending on the duration and latency of the pandemic, and whether or not it worsens they are going to have to adapt, each according to the depth of their own war chest, the size and solidity of their customer base, whether or not they have access to furlough schemes, and the necessity – a possibility in some cases, a certainty in others – of laying off fully trained employees. And that’s if, and it is sincerely hoped that will not be the case, they are not forced to shut down altogether.

Europa Star met some of these suppliers. And we found that while they all have a reduced workload, their situations are very different, especially between those who depend solely on watchmaking and those who have already diversified. But one shared conviction, which gives reason to hope, unites them all: that the key to overcoming this crisis is innovation.

How things stand

As the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH) stated recently: “Swiss watch exports continued to decline in October (...) Ten months into the year, the sector has seen exports fall by a quarter (-25.8%), pointing to the sharpest decline ever recorded over the last 80 years.”

According to François Matile, secretary-general of the employer organisation for the Swiss watchmaking industry, CPIH, “more than half the industry’s workforce, i.e. between 26,000 and 28,000 people out of a total of more than 50,000 contractual job-holders, are or were working short-time.”

Some companies have already made some workers redundant, others are struggling, and alarming figures are circulating about the number of people at risk of losing their jobs in the near future, which could be as many as 5,000. By way of comparison, during the financial crisis of 2008-2009, the watch industry lost 4,000 jobs. Jobs which were only clawed back starting in 2012.

While the furlough system has so far helped attenuate the effects of the public health crisis – which, in the watchmaking sector especially, have been exacerbated by the pre-existing slump in certain key markets, such as Hong Kong – the end of this state aid will usher in a new period of uncertainty. Then, they will have to rely on their own strengths.

In this somewhat ravaged landscape, the situation of the suppliers is especially critical. Placed downstream, they are bearing the full brunt of the crisis, seeing their orders drastically reduced and in some cases reduced to virtually nothing. According to Alexandre Catton, director of the EPHJ trade show (the 2020 edition of which was cancelled), “some suppliers have lost 20% to 80% of their orders. For the orders that have been maintained, some companies have distributed them over several months to allow to them to keep working and save jobs.”

What is crucially at stake in this very unusual crisis is the health and vitality of the watchmaking fabric that underpins and sustains the whole sector. Added to the possible disappearance of certain suppliers is the concomitant loss of highly specialised and exceptional know-how. Its loss would affect and impoverish the entire Swiss watchmaking industry.

Poor visibility ahead

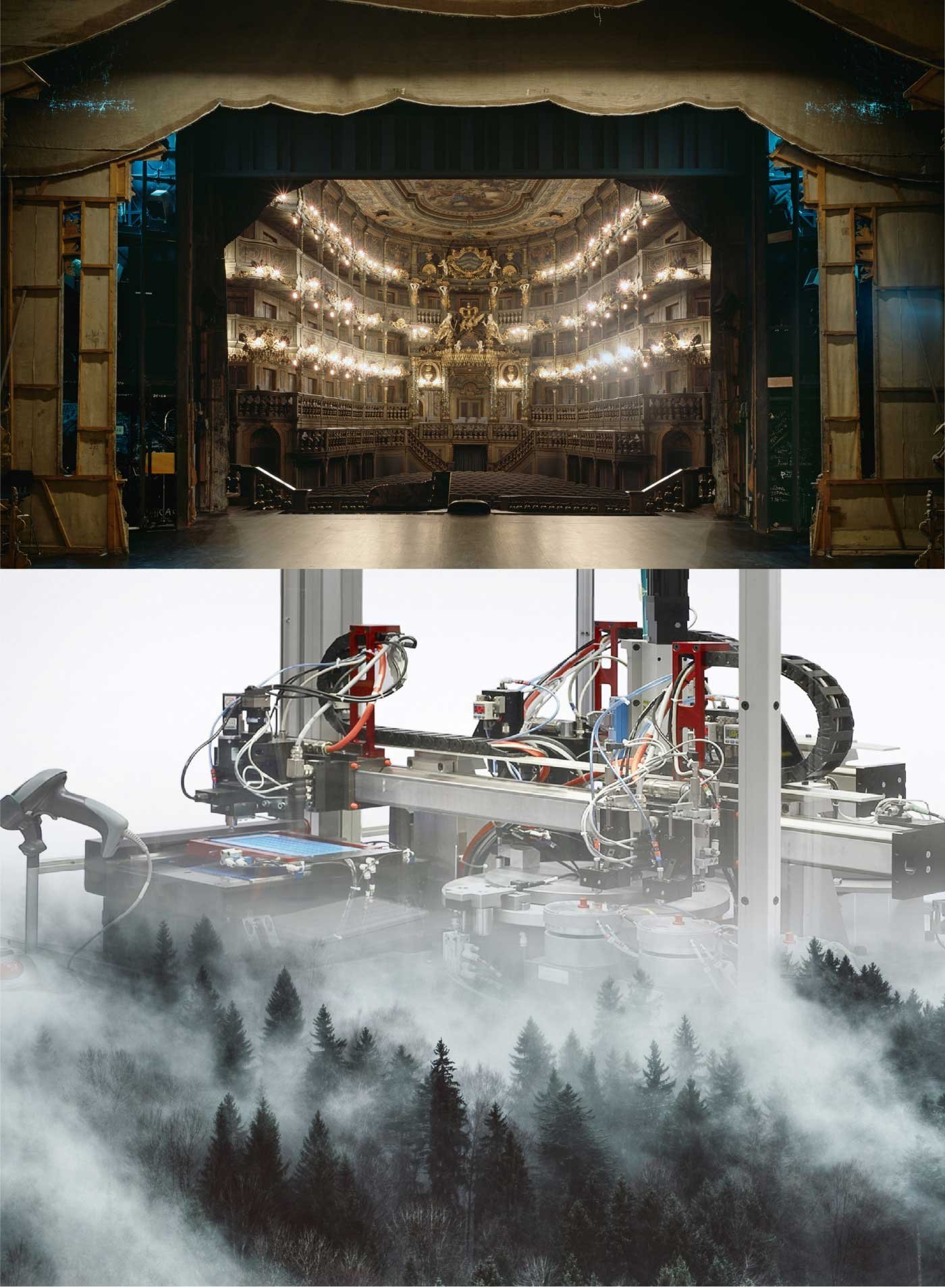

The beautiful valleys of the Jura Arc know something about contrasting weather conditions. The winters are harsh (although, with global warming, increasingly less so), the lakes freeze, then gloriously mild springs succeed them.

At the moment, the forecast is for fog – in the literal and metaphorical sense.

Among the watchmaking suppliers whose workshops and factories are dotted around this bucolic region, where autumn is already well advanced, low visibility is a recurrent topic of conversation, and a central preoccupation for all. Everyone says it in their own way, but the message is the same.

A time for thought, research and innovation

On foggy days, when visibility outside is seriously diminished and lockdown forces you to stay indoors, rather than mope, one may take advantage of the free time to explore certain ideas in a little more detail.

While all the suppliers we talked to spoke of “fog”, they all underlined the fact that this forced break and the period of thought and research it granted them was beneficial for innovation. And innovation has always been one of the sinews of war.

“During March and April, we had to close down completely,” recounts Pierre Dubois (Dubois Dépraz, see portrait here). “Only the design office kept on working. Innovation is the key to overcoming this crisis. And in April 2021, if this dangerous fog has lifted at last, it is innovation that will enable the brands to win market share. During this period of latency when we were free, so to speak, of any production worries, we were able to make progress on projects that significantly enrich the quality and range of our products. With the result that as early as September, we presented three innovations in three very different fields of competence.”

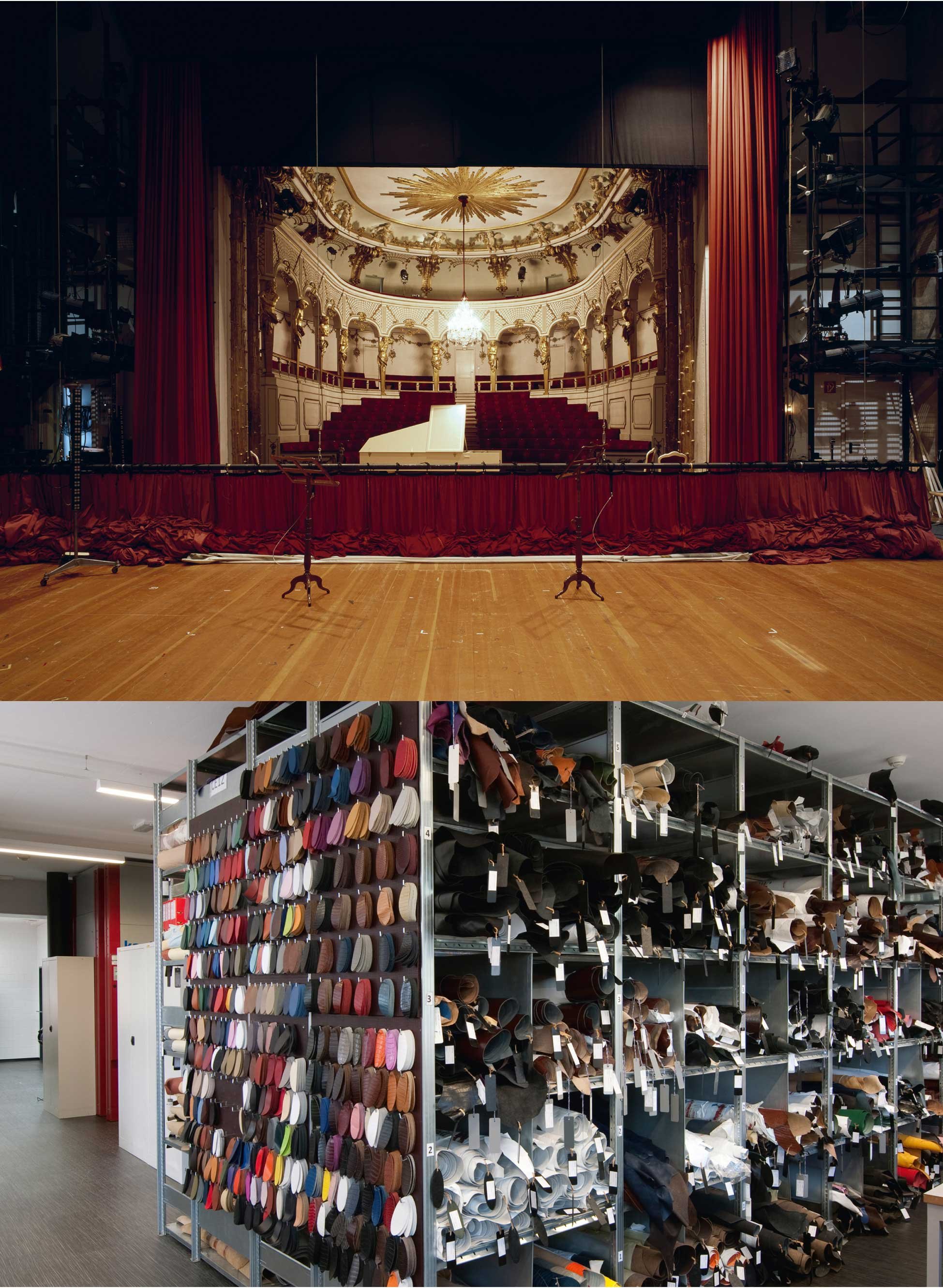

Christian Laufer (Arrigoni-Laufer, see portrait here) and his colleagues in the workshop say the same: “Even though it was and still is a very tricky period, we have to admit that it’s difficult to do research and creation when you’re busy with all the other work there is to do, orders to get out on time. Out of the six months up to the summer, we were able to spend two months doing nothing but research. So we took advantage of that to hone three different innovations in our field of expertise: skeletonisation, bevelling and decoration. A watchmaker is already interested in one of them. But people will only receive you on one condition: that you bring them something new.”

At Brasport (see portrait here), Adrien Brunner, an ex-director of Credit Suisse, who says he “knows most of the suppliers in the Jura Arc”, insists strongly on this point. In his view, “this period when everything was at a standstill enabled us to think more deeply and accelerate R&D. Research and innovation are essential, even if they require investment, which is difficult at the moment. There’s a time lag between R&D, putting the product on the market and reaping the fruit. All the more so since watch straps are consumables (with a life expectancy from 12 to 24 months, depending on usage): the technology behind them has to be distinctive and affordable.”

“What interests me above all is technology and research. But you should always bear in mind that volume improves technology. Here, we’ve produced up to 6.5 million oscillating weights a year. We went along with everything, we produced idiotic volumes, says Émile Zürcher (Zürcher Frères, see portrait here) with his customary outspokenness.

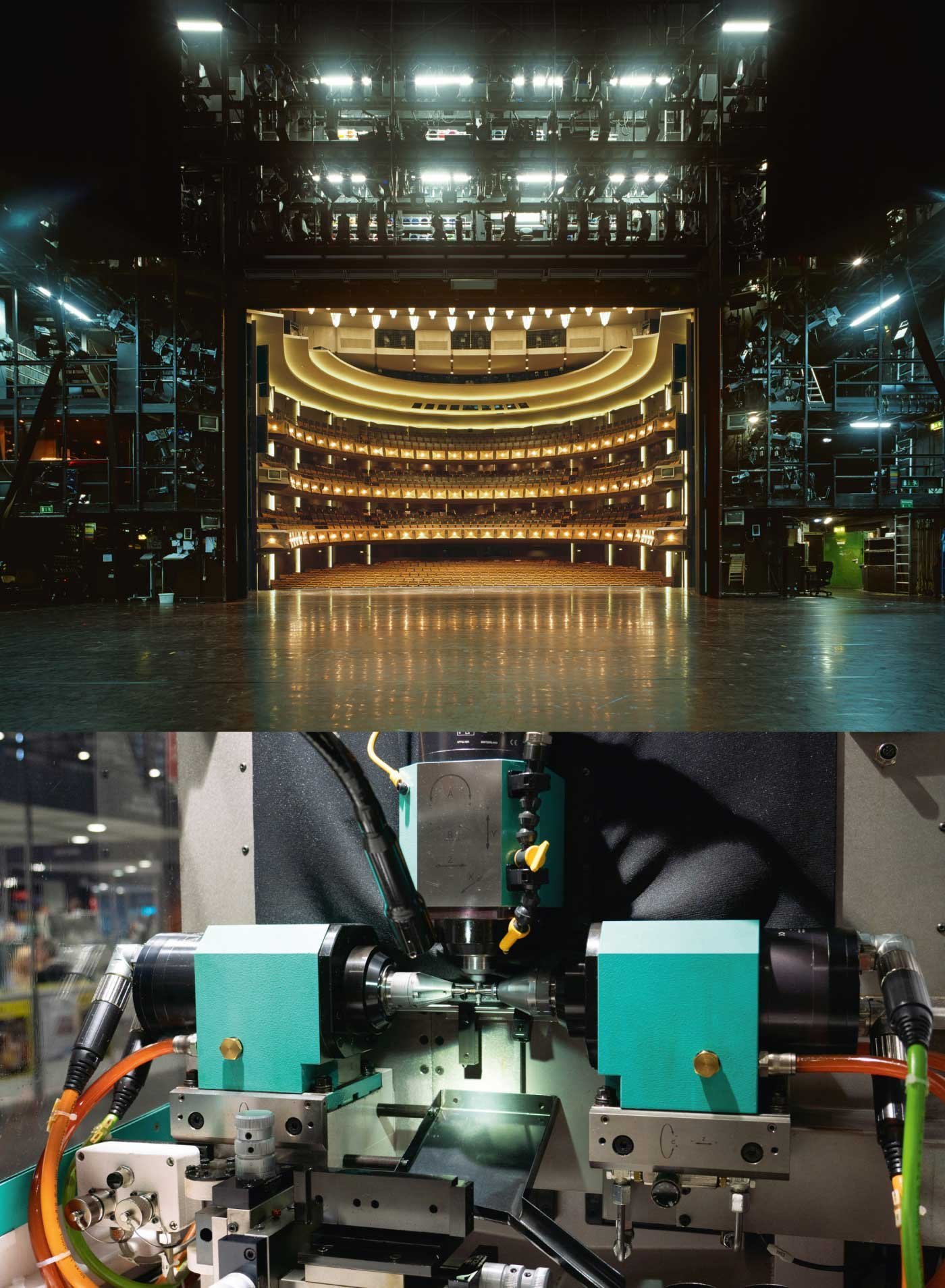

“And today, our delivery volumes are down 50%.” Surrounded by his impressive fleet of high-tech machinery – vacuum furnaces, compacting presses, injection moulding machines, turning lathes, lasers, electroerosion, milling machines, etc. – he nevertheless sounds “pessimistic”, as he admits himself.

“Look at those fully injection-moulded monobloc watch cases made with MIME technology, and those made with ceramic injection moulding, in all colours... Years of obsessive research and development. We have a real technological lead in this field. But Switzerland is the most expensive country in the world. In China, it’s 15 times cheaper and they’re well ahead, in direct competition with the rest of the world. What will be left of Swiss industry soon? Nothing. The system only benefits finance. If I was 30, I’d go to China.”

For the voluble dial-maker Jean-Paul Boillat, “innovation is every day. A dial for Franck Muller requires 180 operations, it’s the face of the watch, the first thing you see and it has to have zero defects. So to have 100 good ones you have to produce 280. But I’ve been passionate about technology since childhood, it’s what motivates me to go on. Here, we have all the tools we need to do everything. And yet the suppliers have zero credentials. We’ve never been well-regarded. I might have heard ‘good work’ twice in 20 years at the most.”

Diversification

R&D, which is essential to maintain or gain market share, also opens up avenues of diversification that go beyond watchmaking alone and provide access to fields that in some cases have become essential for the health of certain suppliers. Medtech, aeronautics, automobile, micromechanics, new materials, new coatings, even armaments... (about which watchmakers say little, but of which Emile Zürcher, who works with advanced materials and is able to produce “missile warheads, ballistic protection, even components for civil and military nuclear power” says: “The military? It’s the only sector left where business is thriving.”).

“One of the major reasons for the existence of a show like the EPHJ is the importance of the technology transfer it promotes,” underscores Alexandre Catton. While, on the surface, watchmaking represents 60% and medtech and microtech 40%, half of the 800 exhibitors work in both fields. This opening up of the fields of action is at the heart of our approach. And it works in both ways because, for example, a medtech specialist like Blösch, which offers all types of coating technology for tools, medical devices, aircraft construction, laser optics, as well as watches, exhibits side by side with the watchmakers. Moreover, firms such as Apple, Garmin and Google come to the show. Diversification is not only essential, but the watchmaking suppliers have the very valuable know-how to achieve it. Here’s just one example among many others: Airbus is planning to build a hydrogen-powered plane by the year 2030. For this major project, it’s going to need components and parts that are much lighter and stronger. That’s a field of exploration which is opening up.”

Relationship with the brands

On the client side, the fog in which the suppliers are trying to find their way has dispersed in some cases, and thickened in others. But for all of them, their programmes have been turned upside down.

The abrupt arrival of the pandemic brought certain production lines to a standstill. In the meantime, stocks already delivered that were in the distribution phase have backed up at the brands. As a result, some projects that had already been launched have had to be suspended while awaiting better days and the resorption of stocks. In this context, has the pandemic profoundly changed the relationship between suppliers and their customers?

Christian Laufer provides a contrasting response to this question. He underlines the fact that a company like Blancpain, one of the biggest customers of the Arrigoni-Laufer collective, “was very fair and told us to carry on as normal with the work that was ordered. That’s 30 items to decorate, each one representing weeks of work. I’m grateful to them.” But, he adds, “not all of them acted like that, and apart from this big order to fulfil, everything else just screeched to a halt!”

Pierre Dubois, however, reminds us that customer-supplier relations had already changed over the past few years, notably with the introduction of the performance metric system called ‘service rate’.

“This is actually a highly structured management system that rates you on three points: quality, quantity and respect of deadlines. It’s a control and evaluation system with audits carried out at your production sites, which assess every stage from order to delivery, including every step in production. In times of crisis like the one we’re all experiencing now, the rigidity of this system is something of a trap, because it’s difficult to make the various necessary adaptations. For example, it forces us to struggle to respect certain delivery deadlines to the detriment of others despite the delay caused by the two-month closure of certain sites. But although this ‘service rate’ is a central issue of debate, the relationship with our customers remains relatively constructive. One of our major customers, for example, suspended rating during the two months of closure. If they hadn’t, we would automatically have seen our ‘service rate’ fall and our rating worsen...”

“What has kept us on course in this difficult context is undoubtedly the diversification and the fact that we don’t only rely on swiss watchmaking. “During the same period, we’ve posted inexpected good figures with the technology brands for which we produce in Asia. But on the other hand, those brands operate differently. Their products have limited life cycles. So they’re less loyal by nature and can drop you overnight. Consequently, there are no long-term contracts, everything is done on a project and tender basis. You have to start again from scratch every time,” says Adrien Brunner of Brasport.

The industrial fabric

What strikes you when you go out and meet the suppliers in their home valleys, at their places of production, is that their deeply ingrained culture, a technical, artisanal culture, is worlds away from that of the current watchmaking establishment, dominated by finance and marketing. They are the ones who roll up their shirt sleeves and get down to the nitty-gritty.

The suppliers to the Swiss watchmaking industry are pragmatists. They serve demanding brands and are themselves demanding, all the more so since high standards are culturally and historically a part of their nature. Innovation, invention, mastery of highly specialised know-how and keeping secrets has always been a real source of pride, and can be calculated in hours and energy expended. Storytelling less so (apart from the convivial evenings of which the people of the Jura know the secret).

“The small and medium-sized suppliers have extraordinary technical skills but not the same know-how in terms of communication,” says Alexandre Catton (EPHJ). “Unlike the brands, they don’t know how to ‘tell a story’. And yet they have so many stories to tell. They have been the sensitive fabric of watchmaking for decades, centuries even, but they operate in the shadows. The brands and the end product take centre stage with their storytelling.”

Historically, the Jura Arc gave birth to types of innovator: the hard-core watchmakers and the madmen of mechanics, in every sense of the term (think Arthur Chevrolet, born on 25 April 1884 at La Chaux-de-Fonds). The two have always worked shoulder to shoulder. And that is how, together, they wove the fabric of the watchmaking supply industry, a fabric that covers all the skills, supplies and services the watchmaking industry needs.

“My father, who worked in the trade, told me never to become a watchmaker. But I was passionately interested in engineering, and I became an electrical engineer,” Jean-Paul Boillat tells us.

“But in our region, you can’t get away from watchmaking. After completing my military service, I heard that Singer, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, was looking for an engineer. I thought it was the Singer of sewing machines. But no, it was – and still is – a dial-making factory. There, they asked me: what can we make other than dials with our production tool? So I stayed there for eleven years and developed a different design office, at a time when electronics and the specific types of display associated with it were coming into their own. But I’ve stayed in dial-making ever since, to go on innovating, but in traditional watchmaking.”

Tears in the fabric

This dense fabric of complementary skills at the service of the brands has been transformed little by little. In their desire for vertical integration, the groups formed thanks to the strong resurgence of mechanical watches gradually acquired skills by taking control of dozens of supplier SMEs. In the same way as they reinvested downstream in their own sales network, the brands ensured the safety of their supply chain upstream.

Holes began to appear in the fabric as a result. Competition toughened, the pressure on prices rose. But when the watchmaking industry was faced (even before Covid) with a decline in attractiveness and new competition from smartwatches, the pertinence of this vertical integration was questioned. All the more so since there was a culture clash between the hands-on artisans acquired by the brands and the “storytellers”. Being an independent supplier or a salaried employee is a totally different work relationship.

Both creatively and economically, all-out vertical integration turned out not to be the best path to follow. Creatively because an independent, tight-knit and friendly workshop is often more inventive and more flexible than a rigid, hierarchically organised body. Economically, if only because it’s up to you to pay the rent on your boutiques downstream, and upstream to absorb the vagaries of the economic situation rather than relying on the independent industrial fabric to take the risk.

The problem for the “fabric” is that this realisation comes at a time when another tear is becoming apparent. The brands’ steady migration towards the top of the market and the gradual decline in volumes in the medium and entry-level ranges has created an imbalance, seriously exacerbated by the advent and success of the smartwatch (no need to repeat that Apple is “the world’s leading watchmaker”). In the current crisis, the high end of the market is, effectively, doing much better than the entry-level and mid-range, which are under attack from all sides and where sales figures are falling with chronometric regularity.

“Clearly, operating at the high end of the market protects us because it’s far more resilient. But we’re seeing huge variations in business volumes,” confides Pierre Dubois.

“We’re anticipating a 25% drop at the end of 2020. Some are down 10%, 15%, others 30% to 40%, or even more. We’re lucky to have a fairly well-balanced, dual activity, with components on the one hand and then the historical additional mechanisms. The two sectors are not developing at the same speed. Many of our additional mechanism customers have suffered more than those who order very high-end components.”

Émile Zürcher draws up a list: “We have metallurgists, plastics engineers, mechanical engineers, mechanics, micro-electricians, IT specialists, labs, technicians of all levels. From 70 people we’ve had to downsize to 50. Deliveries are 50% of what they should be. Thirty-four years ago, I bought this factory with bank loans. Today, I’d be refused them outright. Something’s gone badly wrong.”

Mending the fabric...

This dense industrial fabric of close-knit SMEs, occupying the same small territory, the result of three centuries of history and possessing such a wealth of rare skills, is unique. Essentially, everything can be done here, from the raw material to the end product, whether in watchmaking or microtechnology.

Is Switzerland’s good fortune in conserving a sound industrial base – when so many other European countries have de-industrialised – now at risk of being undermined? Or, to put it more bluntly, is there a risk that the current crisis will “make everything go to China”, as people like Émile Zürcher fear?

We know that this industrial fabric, which has already been through numerous crises, also succeeded in adapting and diversifying, and is by nature resilient. And, as every one of our interlocutors without exception repeated, the key to resilience is innovation.

Today, as Philippe Grize director of Haute-École-Arc Ingénierie, an engineering school for the entire Jura Arc, puts it: “New industrial imagination is needed.”

And this requires a deeper understanding of digital culture. But, paradoxically, “after the standardisation and globalisation of production, Industry 4.0 will enable relocalisation and a return to a form of craftsmanship, industrially produced but highly personalised and responding exactly to the customer’s demands.”

A reversal of perspective which could well redesign the entire industrial fabric of the Jura Arc.