abrique: a word we associate with watchmaking’s original, pre-industrial ecosystem with, at its heart, Geneva and a hive of hardworking artisans. These cabinotiers – watchmakers, stone-setters, fitters, machinists, enamellists and chainmakers – were pieces in a puzzle, each contributing to a whole in an improbable yet productive harmony. Geneva’s watch industry owes much of its international renown to these qualified independents who came to Switzerland seeking refuge from religious persecution in their native France.

It would be no exaggeration to borrow this term, Fabrique, to describe contemporary dial production. The map (below) of 23 dialmakers shows that they are located within the Arc Jurassien, mainly in the cantons of Neuchâtel and Jura. This traditionally industrial region has demonstrated its remarkable capacity to withstand cyclical economic crises.

Such a concentration of dialmakers is to be expected. These small and medium companies cover a broad industrial spectrum – manufacturing of machine-tools, electroplating, machining, stamping, cutting, etc. – and are vital to the growth of mechanical watchmaking.

Europa Star presents seven portraits of companies creating the face of Swiss watches.

1/7 | JEAN SINGER & CIE: LEADING INDEPENDENT

Just as certain artists choose to sign the back of their work, the name JS Singer inscribed on the reverse of a dial is itself the indication of an exceptional timepiece. A leading light of the Swiss watch industry, Jean Singer & Cie SA is one of the few still independent companies, more than a century after it was established.

Its workshops are equipped with some of the most cutting-edge machines of any dialmaker, and while a purpose-developed computerised system manages production flow, the vast majority of processes are performed by hand. Tradition, training and transfer of skills underpin Joris Engisch’s mission: that Jean Singer & Cie SA should remain an independent family firm.

-

- Inspecting the finish on a polished dial

- © Jean Singer & Cie / Patrick Schreyer

Engisch shies away from the media spotlight but the company he manages and wholly owns is impossible to ignore. Since its creation in 1919, Jean Singer & Cie SA has braved many storms, risen from the ashes of a devastating fire and, most importantly, resisted the siren song of potential buyers when, in the space of a decade, virtually all its counterparts relinquished their independence.

-

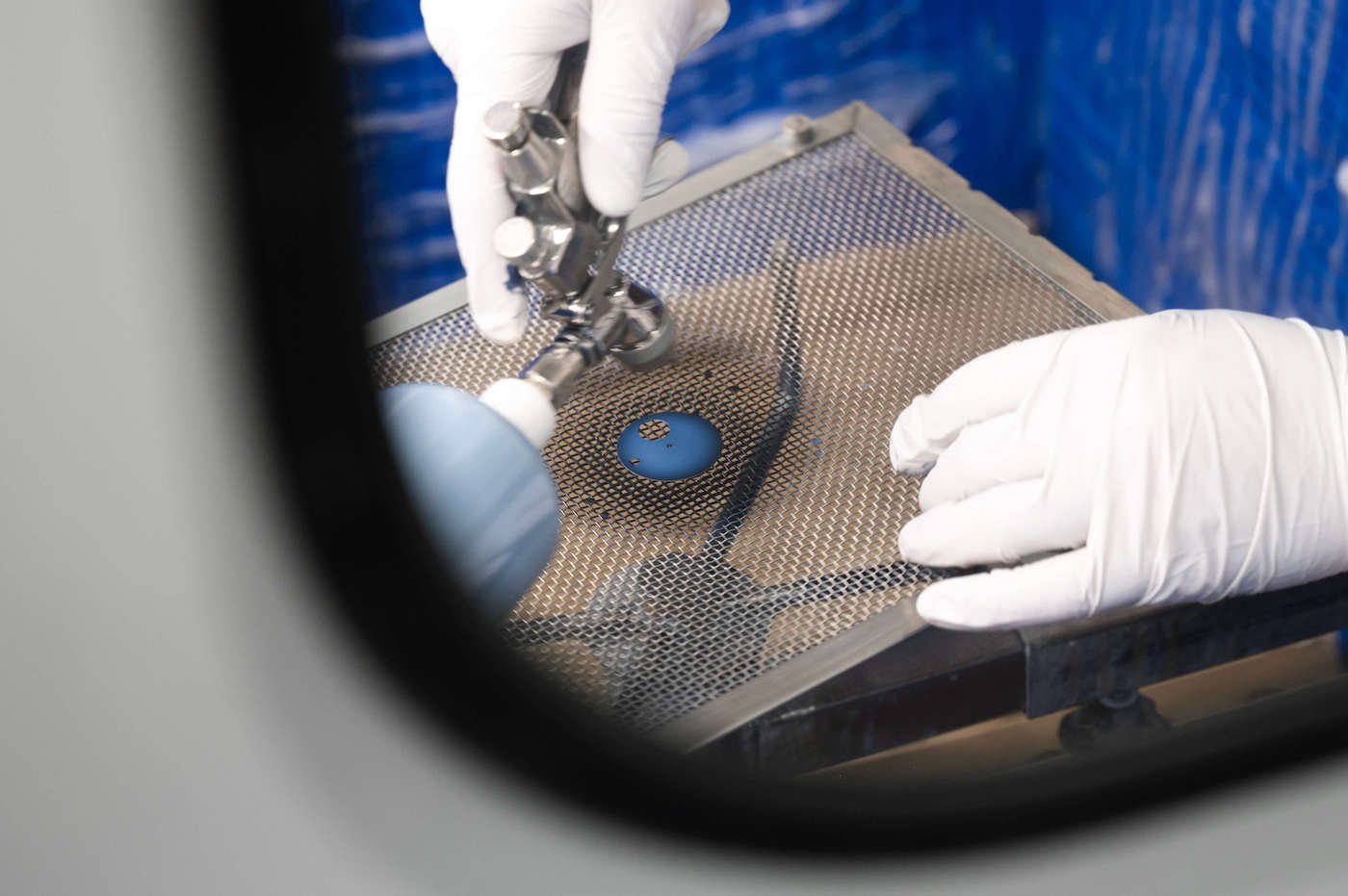

- A technician wearing a protective mask and gloves prepares to apply lacquer using an airbrush

- © Jean Singer & Cie / Patrick Schreyer

As well as being sole owner of Jean Singer & Cie SA, in Boudry, Joris Engisch is co-owner of Someco SA in La Chaux-de-Fonds and Siam Dial Co. Ltd. in Thailand. Together, these three entities produce over 1.5 million dials a year: a remarkable figure that makes them world leaders in high-end dial manufacturing. We sat down with Joris Engisch to discuss the company he has led since 2007.

Europa Star: Jean Singer & Cie SA is over a century old. What’s the secret of this longevity?

Joris Engisch: The company’s founder, Jean Singer, and later his sons were true entrepreneurs, as was my grandfather, Rolf Engisch. He was at the head of the company when it was destroyed by fire in 1957. My father gradually reduced the number of clients from 150 to around a dozen. His idea was to best serve the finest Swiss watch brands and thanks to this our business has thrived and grown since the 1990s. He believed in quality over quantity. We work with the same partners as we did 30 years ago and have built strong and close relationships with them.

There must have been offers to buy the business?

Most takeovers took place in the early 2000s, for example when Rolex bought Beyeler & Cie in 2000, or when Cadrans Flückiger was acquired by Patek Philippe in 2004. In 2007 my father was hesitating over what to do. That’s when he asked me if I wanted to join the business, which I did. I’m now the sole proprietor. If my children have the competencies and the desire to do so, they can carry on the tradition.

-

- Appliques and their feet are machined from coiled metal strips

- © Hubert de Haro / HDH Publishing

What can you tell us about production capacity?

We employ 375 people at our new site in Boudry [compared with 260 in 2021]. It’s a brand-new building that was completed in 2021 and designed to better serve our clients, with around 30% more production capacity. Even then, we’re already outgrowing the space. Our order books are full up to the end of 2024. Plans to extend the building are underway, normally within the next five years.

I also co-own Someco SA, which has moved into our former premises in La Chaux-de-Fonds. [As well as dials] the company makes hands and is becoming an important player in this sector. We recently finalised our takeover of Li Calzi SA which makes blanks, also in La Chaux-de-Fonds. This will enable us to increase our capacity for stamped dials and offer new services.

What about training, particularly manual skills?

For certain professions such as machine operator or electroplater, there are courses which lead to a national diploma. For the others, we train staff in-house over a period of six to twelve months. Most of the processes that require tweezers, such as fitting appliques, are acquired in-house and demand a level of concentration and dexterity that can only be achieved through months of learning. Ultimately, our success is the result of a chain of multiple and meticulous operations, at the end of which we deliver a dimensionally and aesthetically flawless dial. Of course, it’s like cooking. It’s not because you know which ingredients and which method to use that the result will always be something you would want to serve!

-

- Brush wheel with German silver bristles, for sunray decoration

- © Hubert de Haro / HDH Publishing

POf the dozens of stages dialmaking involves, which do you consider to be the most essential?

Anything relating to surface treatment, finishing. There are five main categories: electroplating, PVD/CVD [physical vapor deposition/chemical vapor deposition], varnish, lacquer and inlays such as stone, mother-of-pearl or wood.

Are today’s dials more artistic?

The beauty of our profession is the ability to combine the various types of finish for endlessly different results. This is where our unique expertise comes into play; expertise developed over generations and constantly improved for the past one hundred years. The dials we make today are more “technical” than in the past. Often a dial is a combination of several textures and/or colours. At each step it has to be protected, prepared, machined, coloured then “unprotected”, ready for the next stage. These operations can follow on indefinitely. Getting a dial right first time is a highly complex process.

Was Jean Singer behind the development of PVD?

The technique didn’t originate with us but we were the first to use it on dials for aesthetic purposes. For one of our biggest clients – Rado – back in the 1960s we developed a means of applying a metal track to a sapphire crystal so it could be brazed to a ceramic case. Around then, another prestigious client was looking for a blue that would remain stable over time.

By successfully using PVD on our dials, we engineered a major breakthrough in surface treatments. In practical terms, titanium is evaporated in a purpose-made vacuum chamber. We then introduce a precise quantity of oxygen to create titanium oxide which deposits itself on the dial surface in nanometric layers [1/1,000 of a millimetre]. Depending on the thickness of the finished layer, the incidence of natural light changes the colour the eye perceives. This technique enables us to fundamentally reproduce every colour of the rainbow. Our “Bleu 5 Singer” blue is well-known in the watch world.

-

- Finished dial in “Bleu 5 Singer” PVD

- © Hubert de Haro / HDH Publishing

Where do you see the business in three years’ time?

Demand is strong and we are finding it hard to keep pace, because we lack the capacity but also because the dials we make are more and more complex. By some miracle, it seems neither armed conflicts nor economic crises have dampened the appetite for the finest Swiss watches or for luxury in the widest sense. We are fortunate to work with major brands that are well established on all five continents. This shields us from local crisis and enables us to plan our long-term development.

I’ve also noticed that brands, including the ones that own a dialmaking company, are looking to diversify their sourcing. This puts them in a position to meet additional demand or deal with unexpected circumstances. Also, project managers enjoy talking with independent professionals such as us, rather than thinking inside one box. As in the past, our design office remains a source of innovative proposals and solutions for clients.

How are you adapting production to changes in environmental legislation?

We have always shown respect for the surrounding region and are continually measuring our environmental impact. To give one example, air and rinsing water from our fully renovated electroplating workshop is recovered and treated in a closed-loop. In 2021 we were named Switzerland’s third most eco-responsible company [after Logitech and Chocolats Camille Bloch], well ahead of our clients!

-

- Tiny feet for appliques are stamped from a block of metal

- © Hubert de Haro / HDH Publishing

Aladdin’s genie has granted you two wishes. What are they?

First and foremost, I’d like our company to remain independent and carry on the family legacy. As sole owner, I’m convinced this is the best way for Jean Singer & Cie SA to retain its independence, which benefits watchmaking’s industrial fabric, too. Secondly, I would like to continue to grow the company. We still have a lot to do if we are to measure up to our prestigious clients’ expectations, both technical and aesthetic. We also need to improve our capacity for innovation and offer a wider array of creative solutions.

2/7 | METALEM: THE INDUSTRIAL ARTISAN

Thierry Junod is at the head of Metalem, which employs 200 people across three sites – two in Le Locle and one in Val-de-Ruz – with an average annual production of 250,000 dials. This quietly assertive manager knows the company, founded in 1928, inside and out, having begun his career there 25 years ago before moving to other positions.

Since his return, Metalem has grown considerably; the result of clear positioning; responsible, people-focused management and a favourable economic climate. As one of the handful of dialmakers in business for the past one hundred years, it has supplied every watch brand at some point in their history.

A winning combination

Metalem stands out for its capacity to produce, in Thierry Junod’s words, “complex dials requiring a long series of processes, in non-negligeable quantities.” This can mean several hundred of the same dial and would not be possible without proven industrial experience combined with more than 40 specialisations (think of it as ready-to-wear meets haute couture).

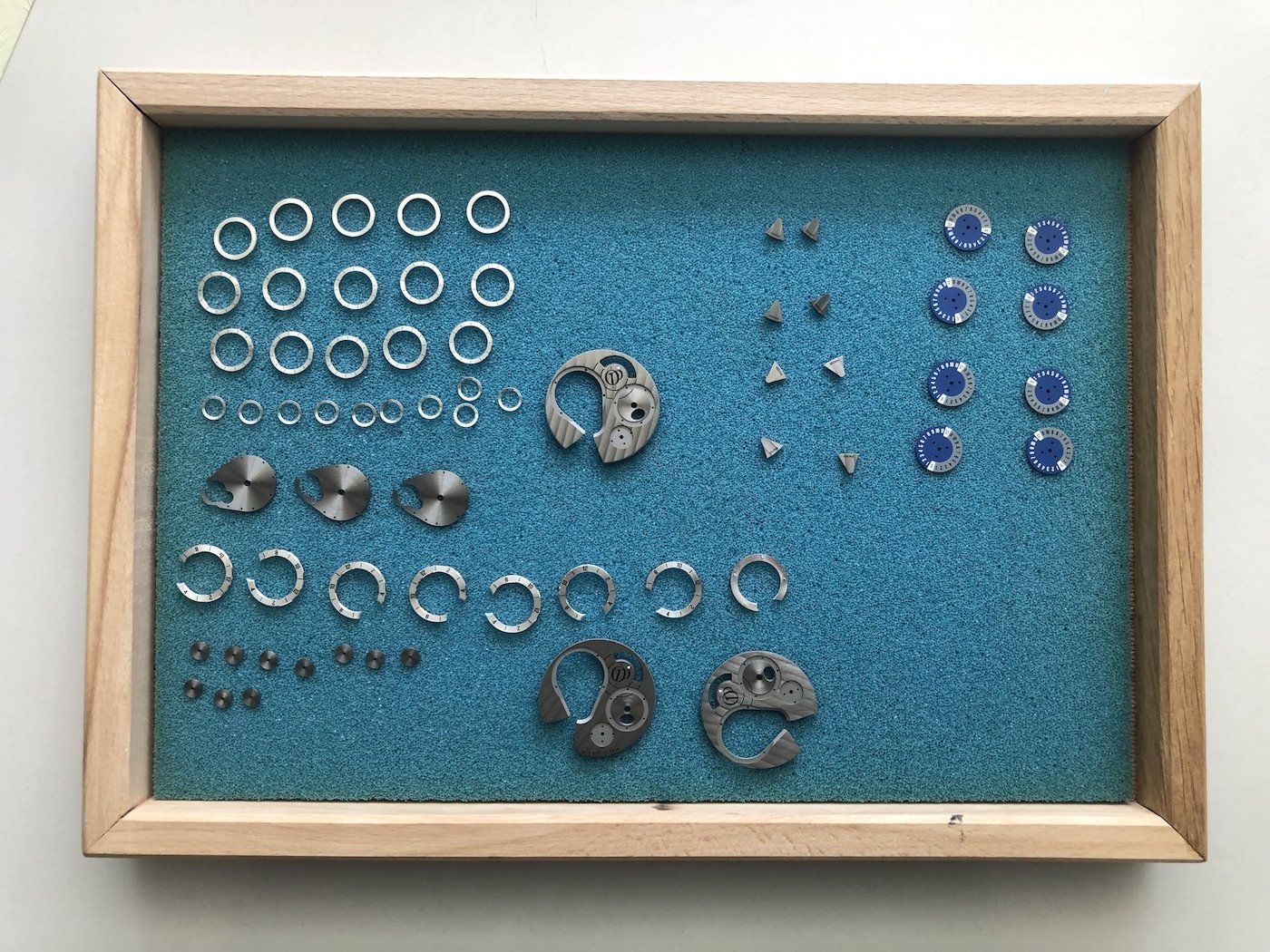

-

- Application of Swiss Super-LumiNova® luminous pigment to appliques

“For months we’ve had to deal with a labour shortage,” continues Junod, whose response is typical of his management ethos: “Whenever we can, we prefer to hire people on permanent rather than temporary contracts.”

Employees are engaged in finding solutions to the crises that are part and parcel of “the history of outsourcing”. The assurance that their job is safe is key to performance, in a context that swings from euphoria to anxiety.

An aesthetic revolution

A huge shift in mentalities has also driven Metalem’s spectacular growth. Whereas black and silver were once the only acceptable shades for a dial, with the occasional exception to “add interest to displays”, the market has seen what Junod describes as “a complete reversal in trends”. The visual is now as important as the mechanical.

-

- Traditional honeycomb guillochage

Having invested massively in movements, brands and groups are now putting dials front and centre: a sophisticated dial, at an average price of CHF 300, will always catch the eye.

Thierry Junod welcomes this opportunity to fulfil the needs and expectations of clients who he says are showing a closer interest in dial production and a greater appreciation of “the complex processes dialmaking involves.”

3/7 | LES CADRANIERS DE GENÈVE: UNCOMPROMISING INNOVATION

François-Paul Journe is a rare bird. In 2000 he officially launched Les Cadraniers de Genève in Meyrin, when he had only just set up his brand, F.P.Journe Invenit et Fecit (and introduced the first ever wristwatch with a tourbillon and a remontoir d’égalité).

Coming from a man known for his stubborn determination, this was no surprise, but friends and colleagues knew this single-mindedness, and a good dose of creativity, would set the venture in good stead. Since June 2023, Les Cadraniers de Genève’s thirty-some employees have worked out of new facilities, crafting high-end dials, from one-offs to small and medium batches, in addition to providing restoration and after-sales services.

-

- Les Cadraniers de Genève and Les Boîtiers de Genève moved into new facilities in Meyrin, on the outskirts of Geneva, in June 2023

A simple premise

Since his early days as a watchmaker on Rue Verneuil in Paris, François-Paul Journe has been convinced of one thing: “The dial is the face of the watch. If you outsource your dials, your watches will have the same face as the rest.” Putting words into action, in 2000 Journe partnered with Cédric Johner and Harry Winston to establish Les Cadraniers de Genève.

He later bought out his original partners and opened the company’s capital to Vacheron Constantin, buying back its share in 2016. Now in complete command, he still accepts orders from other entities and, while his inventiveness is universally acknowledged, the aesthetic consistency of his dials has largely contributed to his renown.

Avant-garde

Before François-Paul Journe, no-one had dared put exposed screws or metallic surrounds on a wristwatch dial. Delicate sanded finishes and grené accents illuminate an elegant landscape, host to a large digital date, moon phases or another complication.

He delights in introducing subtle references to a culture that is directly inspired by his masters, Janvier, Breguet and Berthoud, showing as much as he alludes to a glorious past and avoiding the trap of bland, uninspiring nostalgia. More and more, François-Paul Journe dares.

-

- Polishing a Chronomètre Bleu dial after lacquering

No doubt the turning point came in 2008 with the introduction of the Chronomètre Bleu; the first Invenit et Fecit watch whose showpiece was its dial. Launched to industry acclaim, its hypnotic blue heralded a new era of uncompromising innovation.

The watch’s commercial success confirmed Journe’s intuition. Collectors enthused over this avant-garde aesthetic and constant innovation, from the entirely luminescent dial of the Élégante up to the highest summits of the FFC (Francis Ford Coppola). A composition of multiple facets – metallic, artistic and horological –, its dial is a demonstration of force; an alliance of handcrafting, imagination and technical prowess. It owes its existence to the studio of the talented engraver Jeanne Valentine Ulrich.

-

- Soon the fingers on these hands will be counting the hours on the astonishing F.P. Journe FFC (for Francis Ford Coppola)

Maker and restorer: the heir to Stern

During a conversation with Dr. Helmut Crott, the author of The Dial – The Face of the Wristwatch in the Twentieth Century confessed that, to his mind, Les Cadraniers de Genève were the veritable “heirs to Stern Créations». Indeed, François-Paul Journe’s company conserves the innumerable catalogues of Stern Créations, drawing knowledge and inspiration from these unique paper archives to identically restore dials dating from the 1930s to the present day.

-

- Transfer or pad printing uses a silicon or, as shown here, gelatin pad

Restoration is a rarely encountered skill in contemporary dialmaking that requires in-depth knowledge of the original piece and the expertise to put this knowledge into execution. Often, dozens of new plates must be made to restore or replicate a single dial.

Rare skills under one roof

Given the improbability that one company can master the dozens of specialist skills which dialmaking requires and possess the corresponding equipment, other “high-end” makers – ones that produce no more than 10,000 dials a year - habitually outsource certain stages, in particular the manufacturing of appliques and enamelwork.

-

- Visual inspection

Not Les Cadraniers de Genève, where a surprising number of disciplines cohabit under one roof. A visit to the facilities in Meyrin takes in workshops for machining, decoration, electroplating, lacquering, pad printing, gem-setting and enamelling. Improbability, yes. Impossibility, no. Not for François-Paul Journe and Les Cadraniers de Genève.

4/7 | COMBLÉMINE: “NOT SO FAST!”

Môtiers and Saint-Sulpice form part of the municipality of Val-de-Travers. Both towns also share a connection with Kari Voutilainen. In 2014 the watchmaker bought Dialtech, based in Saint-Sulpice and part of the Vital Morel Décoration Horlogère (VMDH) group which had declared bankruptcy following the death of its managing director the previous year. He renamed the company Comblémine, after the street in Môtiers where he was living at the time.

-

- A block of resin protects areas of the dial

- © Hubert de Haro / HDH Publishing

The company was manufacturing around 20,000 dials a year; an amount far in excess of Voutilainen’s needs. Now synonymous with very high-end production, Comblémine employs 23 people and makes between 600 and 800 dials annually. Voutilainen, its “parent company”, accounts for just 10% of revenue.

A longstanding friendship

Kari Voutilainen and Christophe Beuchat go way back. The pair met in the early 1990s when both were employed at the restoration workshop of movement-maker and restorer Parmigiani Mesure et Art du Temps, established in 1996 and owned by the Sandoz Family Foundation. The start of a long friendship.

When Comblémine’s managing director retired in 2017, Kari Voutilainen offered the position to Christophe Beuchat, who had set up as an independent. The newly minted director was given carte blanche and, as he readily admits, had to “learn all there is to know about dials.”

Less is more

Beuchat, who by now had gained solid experience as a movement constructor, was surprised by what he discovered. “The route sheet [a sequence of operations in manufacturing] for a movement plate takes up half an A4 page compared with two full pages for a dial.”

His first decision was to focus machinery and skills on key phases in production, choosing to work with third parties in areas where “others were much better.”

Machining: the cornerstone of production

He also realised the vital importance of machining, the first step in the production process. Technicians operating CNC machines take charge of the raw metal when it arrives at the machining workshop. “The basis of all our work is a clean, flat plate with no burrs,” says Beuchat.

The reason for this becomes clear further into the production cycle, as treatments such as hand-chamfering, polishing, satin and sunray finishes, sanding, lacquering or Côtes de Genève can only be applied to a perfect surface.

Made to measure

Visitors to the facility won’t see any industrial presses or stamping tools. Each dial is produced in-house on CNC machines which are programmed for each new piece. This is an industrial decision, as Christophe Beuchat explains: “When a press tool costs as much as CHF 5,000, you can’t accept an order for three dials.”

This is precisely Comblémine’s aim: to serve a quality-conscious clientele who might well place an order for one single piece. Sometimes these are for nascent projects or young watchmakers who will grow into brands. This willingness to supply a bespoke product is unusual in an industry where most makers refuse orders for less than 100 dials.

-

- Holders to secure dials for hand chamfering and circular graining

Maintaining skills

When Kari Voutilainen took over Dialtech in 2014, he was keen to retain the existing workforce and the benefit of their experience. Today, when recruiting new staff, the company has to contend with the same labour shortage as the rest of the watch industry. Christophe Beuchat remains optimistic, nonetheless. In just a few years, staff have been cross-trained so that in the event a colleague is absent, workflow is unaffected.

As he does his rounds of the different stages in production, from machining to decoration and colour treatments, it’s not unusual to hear Comblémine’s director telling staff, “not so fast, not so fast!” – the guarantee of a perfect end result. Luxury indeed!

5/7 | LES FILS D’ARNOLD LINDER SA: “METICULOUS DIALS”

An electrical engineer by training, Jean-Paul Boillat is first to admit he was “a complete stranger to watchmaking”. Despite this and encouraged by Valentin Piaget, in 1982 he bought Les Fils d’Arnold Linder, a dialmaking company in Le Locle. In four decades, he has transformed this manufacture de cadrans soignés into a solid business, quietly manufacturing “meticulous dials”.

In perfect unison

To say that Jean-Paul Boillat is his company would be an understatement. He is the personification of Les Fils d’Arnold Linder. As managing director, when the business relocated from Le Locle to Les Bois in 2000, he drafted the plans for the new premises. Since then he has overseen procurement of all the CNC machines, robotic laser cutters and other machinery, recruited every one of the 120 staff, negotiated permits with the relevant authorities and knows every inch of the water, air, cooling and rinsing circuits.

-

- Appliques on a rack, after electroplating

Each year he personally selects the 25 tonnes of salt needed to partially descale water that “takes its source 700 metres below ground, in the Saint-Imier valley.” Listening to him describe the different workshops, adding details others might miss, is an absolute delight.

And when the time comes to hand over the reins? Jean-Paul Boillat eludes the question: “A young employee takes between three and five years to even begin to understand the complexity of dialmaking.” He considers the very concept of dialmaker to be a “mental construct”: a dial is the product of multiple and varied specialisations. Retirement clearly isn’t on the cards.

-

- Application of luminescent pigment

Manufacture

Jean-Paul Boillat is as enthusiastic today as when we first met in 2007, when he showed us round the facilities in Les Bois. At that time the company was producing 200 dials a day and wasn’t looking to reach “mass production”. Fifteen years later, the same values prevail: each year between 60,000 and 80,000 dials leave the workshops, which have the capacity to handle 12 to 15 different models per day: something only a rare few, fully integrated makers can do.

There is a tendency, when discussing the watch industry, to make indiscriminate use of the word manufacture, but in the case of Les Fils d’Arnold Linder, it fits like a glove. All the habitual processes, from machining to electroplating to decoration, are performed in-house. More of a rarity, appliques, dial holders, even the equipment for quality control originate within its four walls.

-

- Preparing a mother-of-pearl dial

A single client

Workflows and logistics have been finetuned for maximum flexibility, to satisfy the company’s one customer: the Franck Muller Group. The group’s two co-owners, Franck Muller and Vartan Sirmakes, wanted to guarantee supplies which MOM Le Prélet, a dialmaker based in Les Geneveys-sur-Coffrane, was struggling to deliver. In 2000 they approached Jean-Paul Boillat and suggested taking one third each of the capital of the newly incorporated Société Anonyme.

The agreement has enabled Jean-Paul Boillat to develop production in line with his own ambitions for the company while rising to the creative challenges set by the Franck Muller Group’s headquarters in Genthod. An alliance to everyone’s satisfaction, now approaching its twenty-fifth anniversary.

6/7 | QUADRANCE ET HABILLAGE: VERSATILITY

Quadrance et Habillage saw daylight in 2006. It was established by the Sandoz Family Foundation which, ten years after launching Parmigiani, verticalized production and multiplied investments in manufacturers of components such as cases, balance springs and… dials.

Originally based in Fleurier, in 2012 Quadrance et Habillage relocated to La Chaux-de-Fonds, to premises previously occupied by casemaker Calame & Cie, which had been taken over by Patek Philippe.

Versatility and continuity

Steve Simonetti is an industrialisation project manager at the company. He is part of a 60-strong team manufacturing cases and dials, ranging from one-off pieces to runs of up to 300 dials a day, for an annual total of 10,000 units.

“We have more of a horizontal structure,” he tells us during our visit to the facility in La Chaux-de-Fonds. “Human values are important, as is communication between staff.”

Versatility is key. Staff are expected to double up on skills which, because of the current labour shortage and the lack of specialised training, must be learned in-house. The correct technique for fitting appliques, for example, is acquired “on the job”, passed from an experienced technician to an apprentice.

-

- Aventurine dial

Two lungs

The production process varies little from one dialmaker to the next, as though governed by some universal law, heir to a century of practice. Which is? From the raw material to the finished dial, the metal will invariably go through three stages: machining, electroplating and decoration (including colour application).

Steve Simonetti is adamant: “Our two lungs are machining and electroplating.” While the end customer will gaze in admiration at the perfection of a hand-chamfered angle or a delicately snailed surface, the technician knows that quality hinges on processes taking place upstream. Any burrs or traces, however microscopic, that have escaped the operator’s trained eye might only be detected at the end of a full production cycle. Minimising defects and discards demands absolute focus at all times.

-

- The coloured lines on this dial are modelled on the London underground map. Behind it, the silicon pad used for printing

- © Hubert de Haro / HDH Publishing

A job well done

“We’re a small team producing modest quantities per client, often 30 to 40 dials,” Steve Simonetti concludes. “Created for Michel Parmigiani”, Quadrance et Habillage has neither the mission nor the vocation to expand to an industrial scale.

Machining is carried out entirely on CNC machines, either by milling (material is removed from a fixed workpiece) or turning (on a rotating workpiece). Concentration will never be broken by the thud of presses stamping out thousands of dials.

Quadrance et Habillage’s compact size is seen as serving rather than disserving the company. Steve Simonetti feels confident for the future; a serenity that comes from the belief in a “job well done”.

7/7 | DONZÉ CADRANS: THE ENAMEL MASTERS

Set up in 1972 by master enameller Francis Donzé, half a century later Donzé Cadrans remains true to its origins. The company, established in the Le Locle hillside, in a building once occupied by Les Fils d’Arnold Linder, employs a dozen craftsmen and women who are all specialists in enamelwork.

Inside the facilities, there is not a CNC machine in sight. Only individual benches occupied by highly skilled artisans who are passionate about their craft and rely solely on traditional techniques.

-

- Jars of coloured metallic oxides used for enamelling

The Schnyder effect

Well before his acquisition of Donzé Cadrans, in September 2011, Rolf Schnyder, former owner of Ulysse Nardin, was already a longstanding customer of the company, which had passed into the hands of Francis Donzé’s daughter, Francine Donzé, and her husband, Michel Vermot.

Then as now, Ulysse Nardin embraces enamel and helps perpetuate this remarkable craft through very limited series whose dials deploy the range of techniques – cloisonné, flinqué or champlevé – or dials in a single, plain colour.

-

- Enamel powder is crushed with a glass or agate pestle to reduce its granularity

Grand feu

The technique of grand feu enamel was traditionally used to protect metal dials – gold, copper or brass – from the ravages of time, humidity and light.

The pristine dials we admire on clocks large and small, pocket watches and now wristwatches are the result of multiple applications of metallic oxide, built up into layers which are fired at a temperature upwards of 800 degrees Celsius (hence “grand feu” meaning “great fire”).

With annual production in the region of 1,200 dials, Donzé Cadrans is clearly distinguishable from workshops which specialise in one or other technique. It serves brands, such as Czapek and Lang & Heyne, seeking the assurance that their dials will retain all their colour and brilliance; something only enamel can guarantee. In this respect, as managing director Claude-Éric Jan tells us, the company adheres to “the ancestral principles and purest tradition of grand feu enamel.”

-

- Metal plates coated with enamel powder are placed in the furnace for firing at more than 800°C. The final colour will depend on firing time and the thickness of the enamel layer, giving each dial its unique charm

The butterfly effect

“We buy more than 20 kilos of enamel a year, mainly from Soyer in Limoges with whom we have an excellent working relationship,” says Claude-Éric Jan. Indeed, enamel dials are a wonderful calling card for Soyer, which produces between 200 and 300 tonnes of enamel a year.

There is something about an enamel dial that appeals to the emotions of an audience of watch enthusiasts in search of authenticity. This wonderful art form is an ambassador for watchmaking at its finest. Donzé Cadrans can look forward to many more years of success… then again, its address in Le Locle is “Rue de l’Avenir”!

TIMELINE: A RAFT OF TAKEOVERS