uropa Star: Let’s talk about trade shows…

Xavier Dietlin: Ah, trade shows. A vast subject. If they don’t change radically, they’re doomed, and soon, what’s more.

The big problem for watchmakers today is that young people, their future customers, don’t need to know the time anymore. Everybody knows that, but no matter: we just go on as if it was completely irrelevant. But the wound goes deep, because the very gesture has changed. We no longer turn our wrists towards our eyes; we put our hands in our pockets and get out our phones and tap on them with our fingers. In response to the question “What time is it”, the gesture is different. The very instinctive reflex itself is no longer the same. You could say there’s an old, 20th-century gesture, and a new, 21st-century gesture.

-

- Xavier Dietlin

Can we say people have fallen out of love with watches?

Certainly, or at least there’s been a huge loss of momentum. I often give lectures in art and design schools, like HEAD (Geneva) or ECAL (Lausanne). When I ask the students, nobody wears a fine watch. They’re not interested any more. And above and beyond watchmaking, the young generation isn’t interested in possessing things anymore. They don’t buy cars. If they need one, they rent one.

Is it the fault of the watchmakers?

Changes in society and technology are having an impact, it’s true, but a large part of it is effectively the fault of the watchmakers themselves. The trade shows bear witness to that quite clearly, they’re a textbook example of the ivory tower the watchmaking industry lives in. You often get the impression that the end customer is being ignored, or that they and their aspirations aren’t really being taken into account. We’re in our own little club, with an acute form of self-satisfaction and self-congratulation. Since watches became a financial commodity, the industry has put sales before everything. Profit is the be-all and end-all. Sales are the only thing that count. And as a result, they’ve lost touch with the public. They’ve lost touch with reality.

-

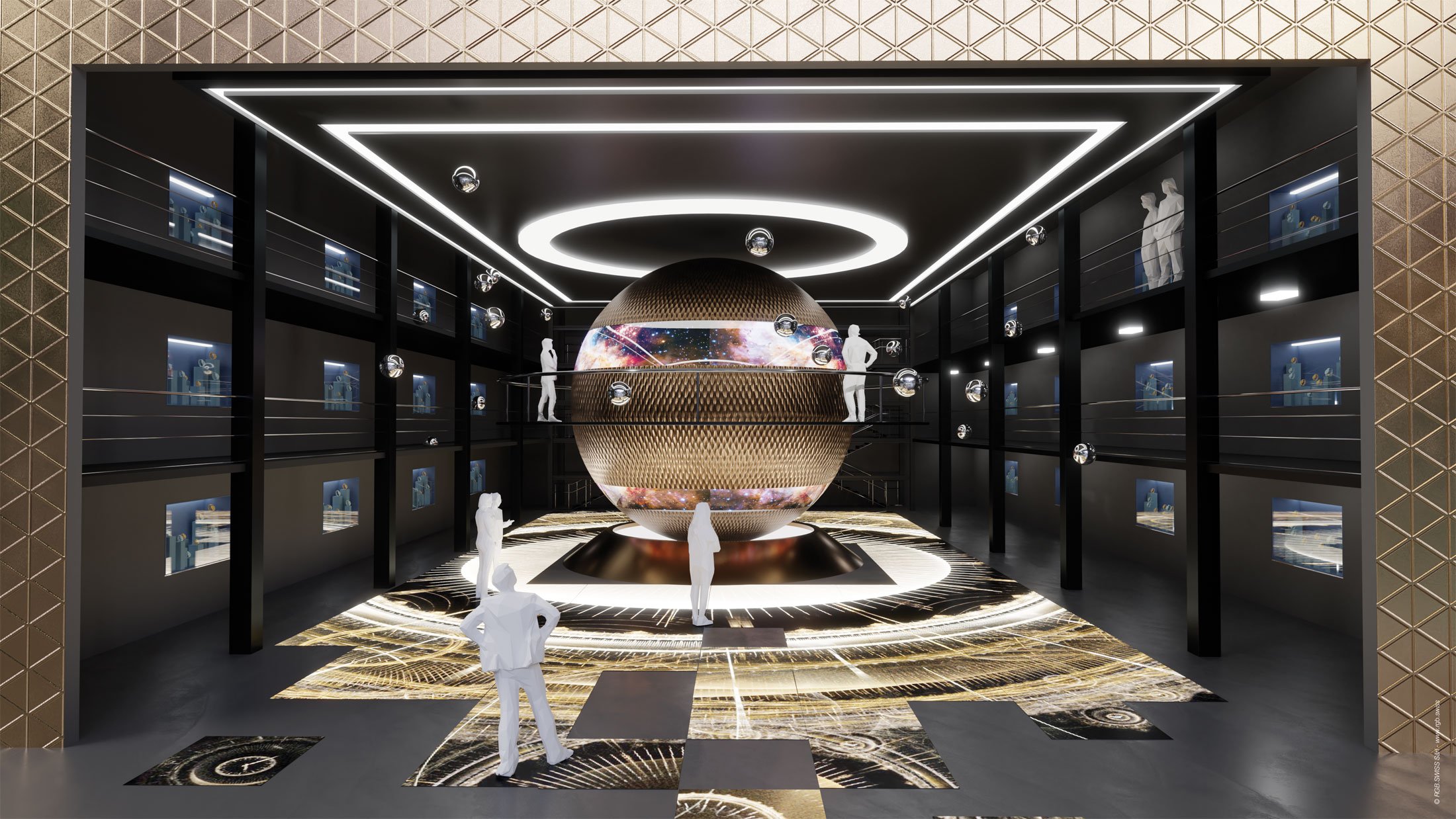

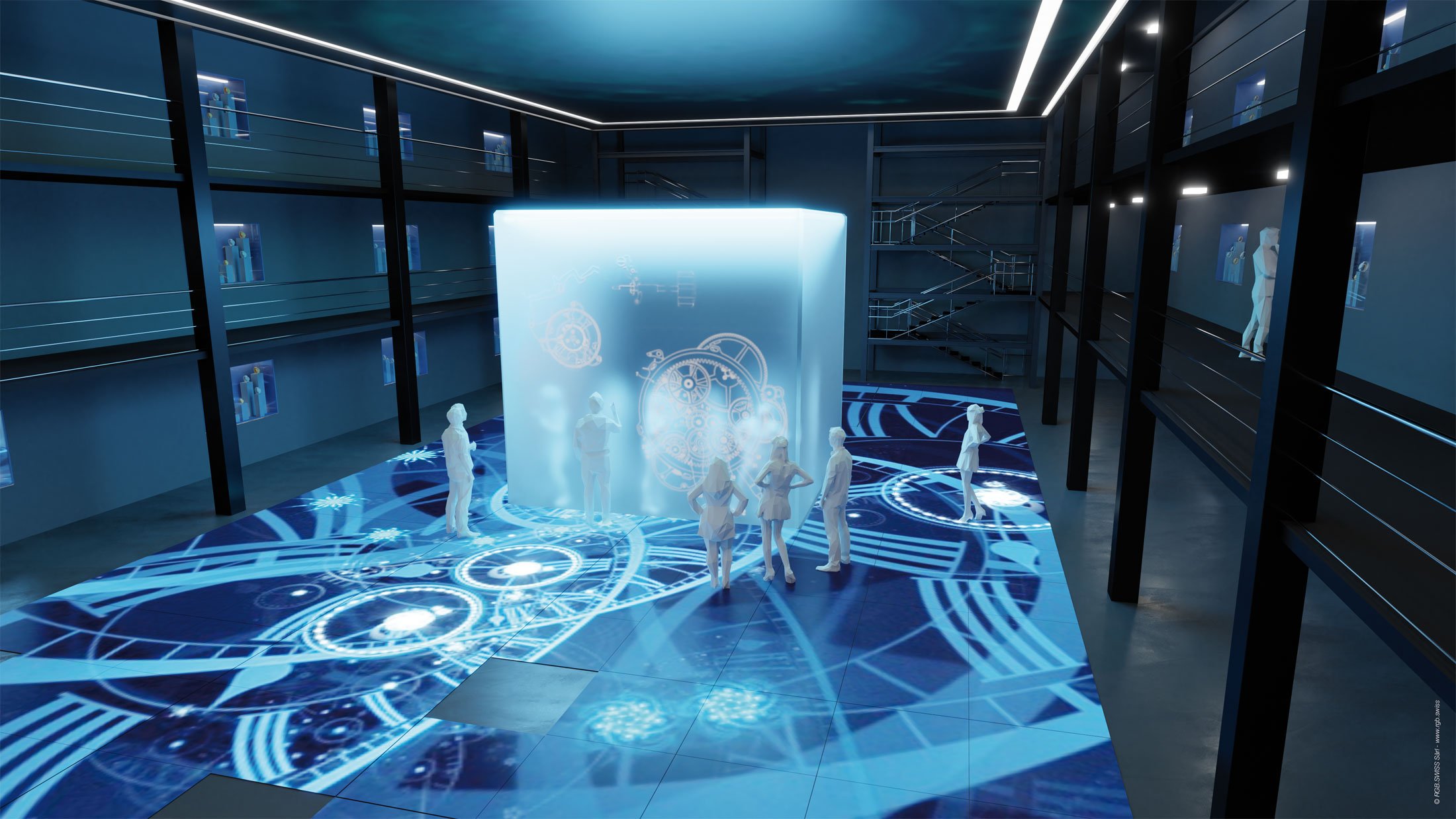

- Xavier Dietlin’s vision of what a trade fair could look like in ten years. “I could imagine an entertainment type trade show that would tour the world, reach out to people. All that’s still wishful thinking – that’s why I’ve called this little image folder ‘Baselworld 2030’ – but time is running out nevertheless,” he says.

But don’t the trade shows play a role of emulation first and foremost? Aren’t they a crucial hub of exchange within the trade?

That should be the case, but it isn’t any more. Nobody really needs trade shows that are closed in on themselves. Inside, everyone is captive. The retailers there are invited because they’re obliged to buy if they don’t want to lose this or that brand, and they’re subject to the dictates of the brands, who impose their choices on them. The media, traditional or otherwise, are captive just the same, since most of them depend for their income on the whim of the brands. No, to survive, the trade shows must absolutely get back in touch with and open up to the public. But if it’s just to see rows of watches lined up in showcases, it’s not worth the trouble.

Before being cancelled due to the coronavirus, Watches & Wonders Geneva announced its opening up to the public with its programme “In the City”, and Baselworld was also making a huge effort to breathe new life into its offering and draw an audience…

Yes, they’re moving in the right direction, but so far it’s a bit of a pretence, a half-hearted kind of opening up. If we really want to keep a trade show, it has to be a real success with the public, above and beyond the economic results. They have to go all out for it.

So what does that involve, in your view?

They have to make people say: Wow! I often cite the example of ArtBasel (ed.: one of the world’s largest art fairs). You come away from that overwhelmed, moved, amused, perplexed, conquered. There are more questions in your head when you come out than when you went in.

To achieve that, you have to make people dream, surprise them, astonish them, perplex them. In other words, you have to lend that single watch, lost in the middle of its showcase, a dimension greater than itself, a poetic, artistic, emotional dimension. The object itself is only 40mm in diameter, but it encompasses and evokes a whole, incredibly rich world.

Watchmaking has the good fortune of being all about an enigmatic and eternal dimension, Time…

Absolutely. Time is an inexhaustible source of thoughts, sensations, emotions, mystery. It’s also the history of fabulous human conquest, which has been going on since mankind began. How to transcribe time, how to measure it, how to build machines that count it, how to decorate, how to shape it. Watchmaking is part and parcel of the evolution of humanity, it goes hand in hand with science, technology, progress, work…

It’s a subject with neither end nor limits, a subject which also poses fundamental, metaphysical, spiritual questions. And that’s not to mention other kinds of time, the time of nature, the time of trees, of stars, to cite just a few examples. A watch is a mythical object. If we want to give back to watches the lustre they’re in the process of losing, we have to share all these evocative aspects of Time.

The buzzword at the moment is “experience”, offering consumers “experiences”…

I don’t like this word, experience. It’s hackneyed, everybody uses it. In our case, I prefer to talk about discovery and enchantment. Going to a trade show should be like going on a voyage, being swept away to another place. Watches are something else, far more than just tick-tock.

Can you give us some concrete examples?

You have to understand that all this is work in progress, it demands time and resources, and above all a complete change of perspective. You have to get beyond the solely commercial dimension and accept that the fallout won’t be quantifiable immediately. The central idea is that only art can make you dream. But I’m not talking about putting artworks on a stand! Just the opposite, it’s about adopting an artistic approach, without intellectualising it, but acting on all the senses, sight, sound, touch, but the olfactory senses too, taste… to achieve far greater intelligence about the product.

Again, an example?

You’ll find some in the enclosed photos I prepared for our interview. But I’ll give you a more detailed example, one I imagined when I was working not for a boutique, but for a kind of private club set up by Audemars Piguet in a tower in Hong Kong. Imagine coming out of the lift and finding yourself right in the middle of Risoux Forest (ed.: a famous state-owned forest overlooking the Joux Valley, where the Audemars Piguet manufacture is located). You’re there, in Hong Kong, and you find yourself flung into a Swiss forest, with its smells, sounds, colours. You walk among the pine trees, which you can touch, snow is falling… You’re going to discover watches, but more than that, you’re going to understand and get a sense of where they come from, see what the watchmakers who work there see, and also where they get their inspiration from. Through the forest, you soak up a culture, you understand that watches don’t come from nowhere, they come from a terroir … And all that is absolutely in phase with the brand’s own communications, which emphasise its roots in the Joux Valley. Even the most urban New York rapper who’s wild about his Royal Oak will be bowled over and understand a bit more about his own watch.

“You’re there, in Hong Kong, and you find yourself flung into a Swiss forest, with its smells, sounds, colours.”

But at the trade show level, the exercise takes on a whole new dimension…

We could very well imagine a joint structure, a framework which is formally identical for all, but within which each brand would offer visitors a different “voyage”, a different way of exploring Time. The brand itself withdraws from the spotlight to offer the general public a space for discovery. As for the indispensable business side, that can be done on the first floor of these “stands”, if you can still call them that, in offices reserved for that purpose.

It’s a tempting idea, but you have to get all the watchmakers on board, and that’s no small matter.

I plead in favour of a united watchmaking industry. I think that it’s also the only way to give it a key role again. But of course, I’m aware that joining forces, a certain form of unity, is not at all a priority for the large groups. Yet increasingly, and for the first time in many years, I’ve sensed on the part of the brand managers a kind of insecurity about the future. What should we do? How should we display our watches? How can we get the new generations interested? You sense that they’re at a loss faced with these questions, yet they’re vital. We have to realise once and for all that consumption has changed, that possessing something is no longer the key issue. And in my view, for the very survival of watchmaking, the only thing that counts is the emotion procured. Little by little, watchmaking has become bourgeois. It has to become audacious again. And the trade shows need to draw in and conquer a real audience.

But this “real” audience you’re talking about is not necessarily in Switzerland.

That’s yet another issue. If we want to stay in our ivory tower, Switzerland is a logical choice. If we want to open up to the largest audience possible, we have to not only dream up a grand, not-to-bemissed, spectacular, magical event, but we have to take it to the audience. I could imagine an entertainment- type trade show that could tour the world, reach out to people. All that’s still wishful thinking – that’s why I’ve called this little image folder “Baselworld 2030” – but time is running out nevertheless. Look at what happened with smartwatches. When they arrived, watchmakers disparaged them, saying it was programmed obsolescence. Well, five years later it’s watchmaking itself that’s running the risk of become obsolete. So it’s time to act. To open the debate. To draw up new perspectives. To experiment with new ways of talking about watchmaking.