e’re all familiar with leap years and their additional day, February 29, to ensure the calendar year doesn’t drift too far from the solar year (which is 5 hours, 48 minutes and 46 seconds longer than 365 days), but what about the leap second? It too aligns manmade time with that of nature but could disappear by 2035, following a decision taken at the 27th General Conference on Weights and Measures, in November 2022.

The leap second reconciles two definitions of time: Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which is the reference for civil time, and International Atomic Time (TAI) defined by atomic clocks. The average of these atomic clocks is calculated by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the authority that defines our system of units of measurement. We want UTC to be in line with astronomical time (UT1), defined by the Earth’s rotation, which is not constant.

-

- For a stegosaurus living 160 million years ago, a day lasted 23 hours instead of today’s 24.

Firstly, Earth’s rotation slows by around 0.02 milliseconds per year (for a stegosaurus living 160 million years ago, a day lasted 23 hours). This is due to the Moon’s gravitational pull, which creates tidal bulges that cause Earth to spin more slowly. Secondly, Earth’s rotation can be affected by major geophysical events, such as the Sumatra earthquake in 2004 or the filling of the Three Gorges Dam in China.

-

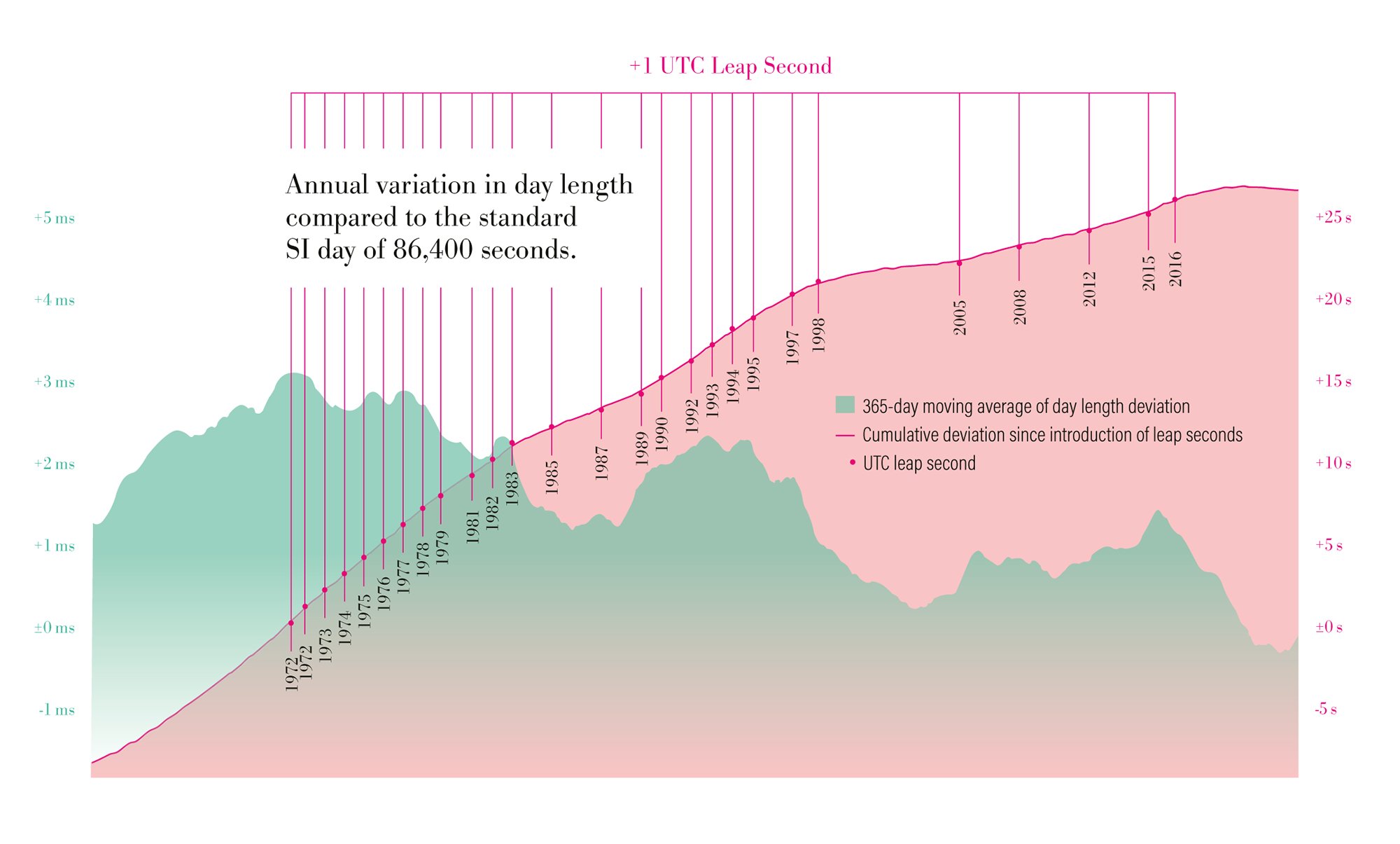

- Graph showing the difference between astronomical time (UT1) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Vertical segments correspond to leap seconds.

How can we combine the precision of atomic time with this astronomical definition of time? The answer is by adding one second: the leap second. This has happened 37 times since the leap second was introduced in 1972, but it could soon be a thing of the past, due to an unexpected phenomenon: observations show that rather than slowing, Earth’s rotation has accelerated over the last three years.

“We have always added a second to UTC and systems are adapted to this,” explains Patrizia Tavella, director of the BIPM’s time department. “Going forward, we may have to take a second off UTC. A huge number of systems would need to be updated, which creates a potential for major technical glitches, not unlike the Y2K bug. The consensus among the international community is that the current tolerance of one second is too restrictive without providing any major benefit.” It’s an opinion shared by tech companies such as Meta, who point out the major technical solutions they have to deploy – and the risks these entail – because of these periodic changes.

A proposal has been made to compound these one-second offsets over a period of one or several centuries until they reach, for example, a full minute. Until then, UTC would continue to sync with atomic time, and the difference with astronomical time could be as much as 59 seconds. Which is nothing, considering that daylight saving has us “jump” an hour in time, in the middle of the night.

Two countries initially opposed this retiring of the leap second. Russia balked at the idea of having to update multiple systems, including its GLONASS satellite navigation system (the equivalent of the American GPS) to accommodate a time difference greater than one second. The United Kingdom, meanwhile, wanted to stick to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), based on astronomical time and increasingly a relic of the past. “The precise time is first and foremost a question of science,” says Patrizia Tavella. “Sometimes, though, it becomes a political matter, too.”